They could’ve complained that it wasn’t their trash, so why did they have to clean it up? But they didn’t. They could’ve insisted on playing in the sand instead of picking up one cigarette butt after another after another. But they didn’t. They could’ve decided that those cans and bottles were too far into the thicket to bother with. But they didn’t. The attitudes and dedication of the 30+ girls that hauled away both small and large debris from a local beach last weekend greatly surpassed my expectations.

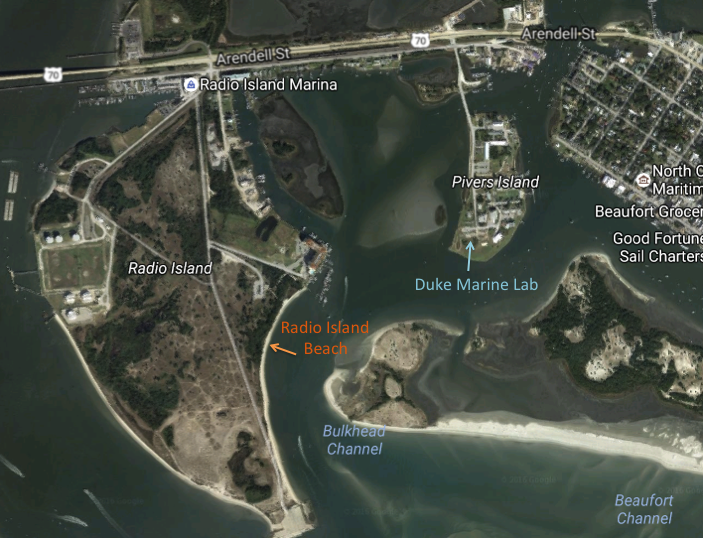

Saturday, October 15th was the the county-wide clean-up day, organized by Carteret County Big Sweep. Big Sweep connects volunteer groups with locations and provides clean-up supplies like gloves, trash bags, and more. Back in August, I contacted Dee Smith at Big Sweep to organize a clean-up for the Carteret County Girl Scouts. We planned for Radio Island Beach.

Prior to setting out with our gloves and trash bags on Saturday, we split into groups of roughly 5 girls per 1 or 2 adults. Each group toted a clipboard with an Ocean Conservancy marine trash data sheet. Our instructions were to document and count everything we picked up. I brought the forms back to Dee at Big Sweep this week, and she’ll enter our data into a database. Eventually everything will be analyzed by the Ocean Conservancy along with other trash data from across the country.

Since the Duke Marine Lab master’s students also had their clean-up at Radio Island just a few weeks prior, I expected there wouldn’t be too much for the girls to pick up other than what may have washed up during Hurricane Matthew. What I hadn’t accounted for was that the girls, being smaller in size, would dedicate their time to squeezing underneath the forested thickets to discover litter piles that were like time capsules from the past.

My group of girls started out on the walkway to the beach, picking up dozens of cigarette butts that people had tossed over the railing on their way to or from the water. We made our way onto the sand and took a right. We didn’t get too far because the girls discovered an overgrown access point to an even more overgrown area of dense branches and low trees.

They fearlessly embarked on unearthing bottles and cans that must have been lying there for years or even decades. Uniquely-shaped amber beer bottles, antique-looking Coca Cola bottles, large clear glass bottles, and soda cans so photodegraded that the yellow-lime colors turned gray with holes spotting the aluminum. Many bottles were home to thick, slimy green and brown biofilms, exhibiting how this debris had become somewhat integrated with the environment. The bottles kept coming, filling an entire large trash bag, and eventually we had to leave without removing all of them. Other items pulled from the forest included a frisbee, a fully inflated inner tube float, building materials, light bulbs, and other food and drink packaging.

Our whole team of Girl Scout volunteers collectively removed hundreds of pounds of trash and recyclables from the beach area. When we gathered at the end, I asked the girls what item they picked up the most. I hoped they would say some single-use item like food packaging so I could capitalize on the opportunity to advocate reusables. But instead they unanimously shouted “beer bottles!” in the same tone kids normally reserve to shout something like “ice cream!” I hadn’t planned on that response, and the girls’ desensitization to such types of abundant debris was somewhat upsetting. I tallied up the data sheets after the clean-up and the girls indeed were right- we collected approximately 136 glass bottles from Radio Island, second in quantity only to ‘small plastic pieces.’

Removing litter is a valuable endeavor, yet in the back of my mind I always think about how the authors of Cradle to Cradle feel about it: that we are merely alleviating a symptom of the major design flaws in the way we make things. We are administering an ibuprofen when what’s really required is reconstructive surgery.

Trash clean-ups are a much-needed start, but there also needs to be greater efforts dedicated to making products that don’t become “trash” and whose materials flow from cradle to cradle instead of cradle to grave. If such products and practices were commonplace then we wouldn’t need to rely as much on consumers to make ethical/environmentally-friendly purchasing and disposal decisions, since the decisions would already be made at the manufacturing step.

This week I walked over Grayden Paul drawbridge several times on my way to the marine lab, past areas that another volunteer group cleaned over the weekend. Already there were cans, bottles, plastic bags, and food wrappers scattered on the side of the road and where people go fishing. Clean-ups and efforts to reduce littering of non-biodegradable trash are parts of the solution, but the way our products are made is another huge area that must be addressed by engineers and chemists. If cleaning up trash perhaps inspires a girl scout to become a green chemist and help redesign the way we produce things, then clean-ups might be part of a solution to the root of the problem after all.