I am already an avid user of eBird, a website and app that allow birders from all over the world to record their data, while simultaneously providing a wealth of data to scientists and conservationists. Given its importance as a citizen science project, I was thrilled to discover eButterfly, a more recent project with the same goals. Over winter break I took some time to identify a few of my butterfly photos, and recorded my first observations.

Picture a hot, muggy afternoon in Central Florida. While on Fall Break visiting family a few months ago, my fiancé and I took an afternoon walk through Conner Preserve, hoping to see a few Florida bird species.

The trail began in a field, grass growing to hip and even shoulder height. Ponds reflected the blue sky to one side of us, but there were no wading birds or waterfowl fishing in the shallow depths. Curving, the path entered scrubby woods full of conifers, live oaks, and the always lovely palmettos. Despite the varied habitats, I had little birding luck. It didn’t help that it was in the middle of the afternoon on a hot day, and other than a circling Turkey Vulture and one or two songbirds, I saw nothing.

However, though the conditions were not ideal for birds, they were very well suited for butterflies. I had bought a guide for butterflies over the summer, but here was the perfect opportunity to focus my identification energies. The wildflowers within the field provided food and cover for the butterflies, and I snapped close-up photographs of two lively and beautiful varieties, with every intention of going right home, flipping through my guide, and zeroing in on the correct species.

But as sometimes happens, life got in the way, and the photos remained un-analyzed within my computer files. I never forgot them though, and on one relaxed Sunday opened the images up once more.

The first butterfly I had seen on my trip to Conner Preserve was orange, with black and white spots along the wings. Pretty, but nothing too out of the ordinary. The second butterfly had wings with a brown background, orange flecks along the top and orange/yellow shading on the bottom, with six eye-like spots.

The latter butterfly was relatively easy to find in the field guide, a Common Buckeye. Sweet, I was 1 for 2. Unfortunately, the orange butterfly was not so easy to find. Why? Because there are tons of orange-speckled butterflies, and I couldn’t make an identification decision. So I called in the cavalry, emailing Will Cook, an Associate in Research here at the Nicholas School and butterfly expert. Luckily he had no trouble, and told me that my orange unknown was really a Gulf Fritillary!

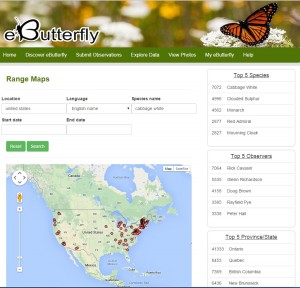

Identifications in hand, I logged on to my new eButterfly account and prepared to submit my observations. The first step: telling the system where I went “butterflying.” Now how cute is that? Following the orderly instructions, I logged both the Common Buckeye and Gulf Fritillary, taking my total recorded butterfly life list up to 2. Once I finished, I found myself exploring the range maps of other species, like the Cabbage White I had identified over the summer in Maine.

Of course, my progress with butterfly identification will continue much more slowly than that of birds, as butterflies are simply more difficult to tell apart. Additionally, there are entire months where I will not get practice, at least while I’m living somewhere with a cold winter season. Still, there is hope! In addition to the resources on eButterfly, I can submit my photographs to iNaturalist, where an expert can help me differentiate the species – for free!

For now, my eButterfly life list is at 2. Watch out summer months, there is a whole new butterfly observer ready to log species!