The wind whipped through the golden grass on a 105 degree June day in California’s Central Valley.

We could barely stand up straight up, hands on our hats, as windmills hummed nearby.

“Careful with the catalytic converter on that dry grass.”

We were worried about fires.

In these conditions, just the latent heat from the carburetor could set the grass ablaze.

“The fire risk in these conditions is off the charts,” one of the Los Vaqueros Watershed officials observes. “We need cattle up here to come knock this grass back down.”

Gareth Fisher, General Manger of B-N Livestock – which holds the grazing lease at Los Vaqueros – nods. He’s been trying to get cattle on this hillslope for a while now.

In Park City, Utah, a month later, it’s much cooler, much greener.

I’m learning about fractals. And grazing.

“The patterns we’re seeing in nature – they’re not linear. Nothing in nature is linear.

“The patterns correspond much more closely to fractals. But the patterns are still there.”

I asked Gregg Simonds, CEO of Open Range consulting, what the fractals tell us.

“Well, you’re an athlete – you know that to improve, you to need work hard for a while, then rest for a bit. Land functions pretty much the same way – for it to be its most productive, you have to work it, then rest it for a bit. How hard you can work the land depends on what it is historically used to.

“It’s all about time and timing of grazing. That’s what we’ve seen over and over again.”

Gareth Fisher and Gregg Simonds are hoping to change not only the way that ranching is done, but the way that it is viewed.

Ranching can be a divisive topic in the environmental community.

You don’t have to travel far to read another author on the Nicholas School blog site to see a well-reasoned view of the environmental evils of ranching.

Bill raises many valid points.

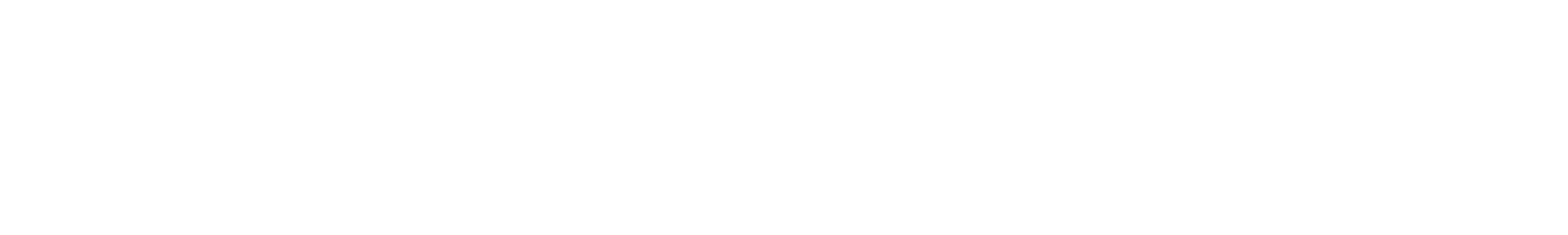

But, here’s one thing about beef. It’s not going anywhere.

Demand for beef may be slowing in the US, but it is growing abroad.

And, whatever happens, demand for beef won’t drop to zero tomorrow.

According to Encyclopaedia Brittanica, rangelands make up 40-50% of the earth’s surface.

Livestock herding provides an income for many of the world’s poor.

Here’s another thing about beef.

Buffalo used to roam the Great Plains before white people extirpated them.

Other ungulates used to roam other parts of the US in far greater numbers than they do today.

Today, we have still have vegetation growing in these landscapes, but fewer ungulate in general.

In order to have a functioning ecosystem, we have to replace their presence with something.

As Laura Jean Schneider, who works at Triangle P Cattle Company, observed in a recent edition of High Country News, ranching can be a form of conservation,

“When used as a creative land management tool — with the added benefit of producing food — our cattle can help sequester carbon, reduce fire fuels, and restore wildlife habitats. That sounds like conservation to me.”

Not a lot of livestock outfits are thinking frequently about their environmental impacts.

However, Gareth, Gregg, and the rest of B-N are.

I worked for B-N in California last summer. They were interested in quantifying the impacts of their grazing activities on the 18,000 acre Los Vaqueros Watershed ecosystem and its biodiversity.

Los Vaqueros has a unique attribute. In the 1990’s, Contra Costa Water District dammed an existing creek to provide additional water storage facilities in the area. By pumping water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, the Water District – has created an artificial lake.

In order to build the dam, the County had to get a permit from the US Fish and Wildlife Service. The Service agreed, as long as the County agreed to conduct annual monitoring for a variety of endangered species found in the area.

Thus, unlike most grazed areas, the Watershed has a long and detailed dataset of annual red-legged frog (Rana draytonii) censuses since at least 2004.

I ran a multivariate statistical analysis looking at the effect of how the intensity of grazing, weather, and sun strength correlated with changes in red-legged frog (an endangered species) population. There was essentially no correlation between grazing intensity and frog populations (R2 = 0.04).

The dataset I used really reflected the effects of the previous grazing leasee (B-N has only had the lease since Nov., 2013). However, it offers a baseline for B-N to compare their own efforts too.

Are frogs really the best thing to study when considering the impact of grazing on the ecosystem?

Maybe, maybe not.

There may be other species or factors that would be better, but the available data was red-legged frog censuses, so that’s what I looked at.

This is the focus of Gregg Simonds’ current work: how to create the appropriate metrics to determine rangeland health that are also easy to measure.

Reminding me of my business school professors, Gregg pointed out that “you have to be able to measure something if you want to improve performance. And you have to do it cheap, efficiently, and effectively.”

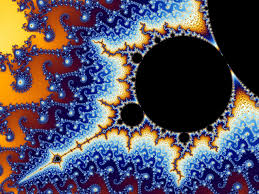

Bare ground, though, is enemy number one.

That’s what Gregg really wants to convey.

“Changing a bare area to a vegetated area, water tends to go in the ground instead of over the ground. It’s an incredibly powerful thing that happens.

“When you lose your soil, what happens? It doesn’t matter if you get a lot more rain–it’s not going to be near as effective to productivity.”

As he once told the Salt Lake Tribune:

“Keep a cow, a horse, a buffalo or a deer in a confined space, and the land will be overgrazed,” said Simonds, a range consultant. “It’s not an issue of how many animals are on a single plot or grazing allotment, but the fact that they’re constantly there.”

Later, he told me “cow hoofprints create depressions in the ground that change its topography. They also ground seeds into the earth. This combination creates the opportunities for seeds to take root, to grow into vegetation, to create the ability to hold water in the ground.”

On my way out to California, I spent some time with ranchers in South Dakota’s Badlands.

One of them told me:

“I mean, look, we’re not trying to exterminate everything down here. We know we are ranching in an operating ecosystem… We just need to be able to defend ourselves… We do want some predators around here – I like them, my kids like them. We’re not trying to get rid of everything.”

Los Vaqueros is part of an annual grassland ecosystem, which in pre-colonial times was maintained through large grazing animals and frequent fires. Post-colonial fire suppression efforts have increased the importance of utilizing grazing animals to maintain ecosystem function and to continue to keep fire risk low.

In July of this summer, Gareth undertook a grazing operation designed specifically to make a fire break on the edges of a busy highway that cuts through Los Vaqueros. It was cheaper than a mowing operation, and of course, also contributed to local food production.

It substantially reduced fuel loads and fire risk.

You can find more about Gregg’s work here and here.