Flip open to TIME Magazine’s December 9th feature article, and you’ll find our own Durham, NC right in the opening sentence. This article isn’t about about food trucks, though. It’s about the U.S.’s steep rise in wildlife populations, which are mingling more and more frequently with humans as our sprawl coincides with their search for food.

The white-tailed deer is a perfect symbol of this population rise, with over 30 million currently in the U.S. According to TIME, that’s an 800% increase from the mid-1900s. Reducing the animals that prey on deer (wolves, for example) and altering the environment are some of the ways humans helped create these population booms. Deer prefer edges, where forests meet open spaces. Clear-cutting has created many of these edges between forests and spaces such as farmland, backyards, and golf courses.

Car accidents, Lyme disease, and crop destruction are the most cited human welfare problems related to large populations of deer living alongside people. Durham is no exception to these problems, and this November the city council passed a deer hunting ordinance. The ordinance allows people with an NC hunting license to shoot deer with bows and arrows within areas of consent, from at least 10 feet above the ground. Although this is a new ordinance for Durham, the Duke Forest has been practicing its deer reduction program for six seasons now.

Deer pose a special threat to the Duke Forest because of the forest management and research that goes on within its boundaries. Browsing deer can influence plant succession, determining which trees grow after thinning and harvesting. For about a 3-month bowhunting season in the fall, the Duke Forest closes off its trails to the public on weekdays. Deer killed during the reduction program are studied to determine health trends among the population.

News of the closure hit me with disappointment and frustration because I run on the Forest trails skirting Highway 751 most days of the week, they are one of the things I am most grateful for in Durham. I was extremely relieved when I found out that Duke Club Running members are granted permission to use the Forest trails during the hunting season.

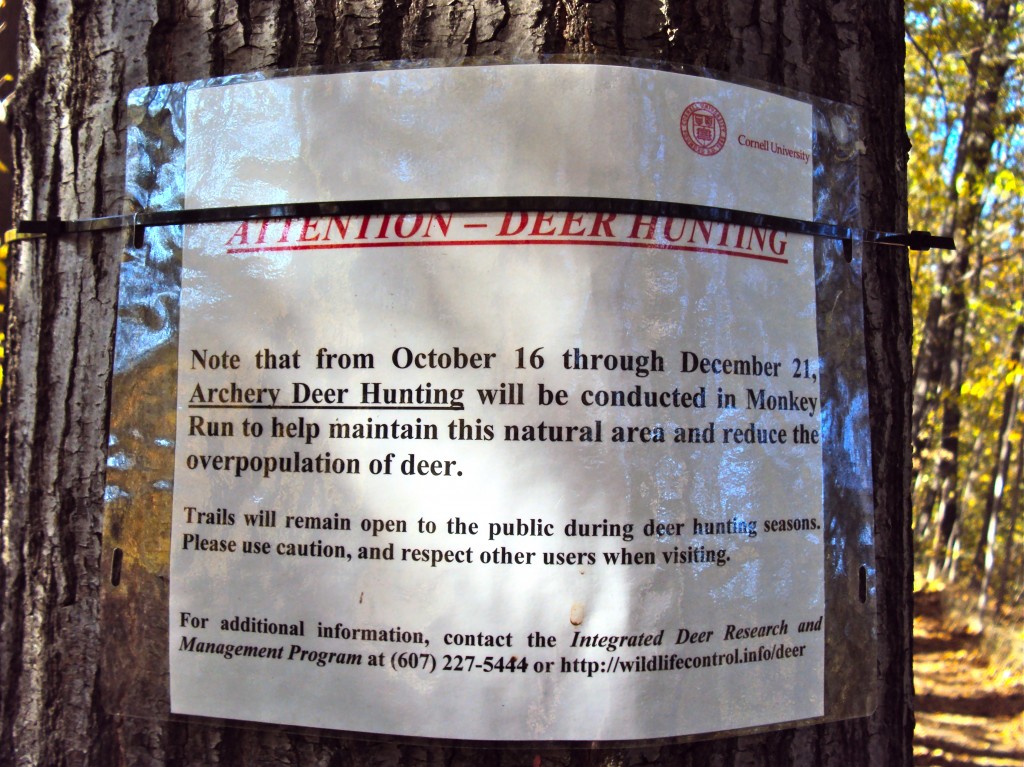

We never met any hunters, but were stopped once at dusk by Forest employees in a pick-up truck who were not informed of our permission. To the delight of trail users, this week marks the end of the hunting season and the removal of closure signs at the trailheads (all photos below are from different trailheads along the route shown above).

[portfolio_slideshow]

Within the past five years, I’ve grown accustomed to overpopulated deer and deer control measures like bowhunting. In my hometown in MA, deer used to be rare enough so that seeing one as a child was exciting. But when I moved to Ithaca, NY I began to regard deer as squirrels- they were almost as prevalent. When talking about deer in Ithaca I usually share an encounter I had four years ago while running through Cornell’s wildflower gardens. Just outside the 8-foot gated fences that prevent deer from eating the flowers, a herd stood munching on leaves. As I approached, cautiously slowing my pace, I wondered when they would back away with concern or scatter swiftly into the forest. Neither happened, because I ran through the group without one of them budging, inches away on either side of me.

Areas in Ithaca have their own reduction and research approaches to overpopulated deer, including fences, crop protection, hunting, and sterilization. Sterilized does are radio-collared to study their behavior and survival. Bowhunting occurs in forests around the Cayuga trails, which our running club frequented. Residents of Cayuga Heights in Ithaca discussed their backyard deer fences on an episode of PBS’s Nature that aired this May. A fair amount of controversy surrounds deer hunting in this suburban community. In May I helped plant tree saplings on a Cornell research farm for a study that is testing different plant protection methods against deer. Deer eat about 7 pounds of food a day, and I learned that the 800 saplings we planted could amount to just breakfast for a hungry deer herd.

Methods for dealing with overpopulated deer (hunting, sterilization, crop protection) cannot undo the environmental alterations we’ve made that have allowed deer to become so prevalent in the first place. Hunting seems to be the most popular control method thus far, but we still cannot predict with certainty how or if reduction methods will solve human welfare problems in certain areas. As John Muir wrote, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” Unintended consequences occur in environmental management scenarios because of complex ecological networks. Ongoing research on deer and the effects of control methods can help with programs in the future.

Hi Sarah,

I’ve been following your blog- very nice work!! I liked both of your articles that I read so far 🙂

I’ve seen a lot of deer dancing around at Cornell as well as U Iowa; I like them, they do likewise 🙂

From a hydrologic point of view, increased deer population might be altering the landscape and hydrology of the region they prevail. Because of their large consumption of grass and crop, they might be limiting the infiltration rate, thereby increasing the flood runoff– not to mention the reduction in available ground water, and hence increase in nutrient concentration and potential decrease in sub-surface-organism population, which can adversely affect the entire region. The differentiated availability of nutrients and possible decrease in root-zone water can affect the grass and crop production.

That is what came to my after reading your article. Any but the well established scientific reasons of deer reduction shall be considered only after meticulous scientific investigation.

I think that there are some critical benefits of deer presence also to society, but no, excess deer may not do good.

Thanks Sarah for writing your thoughts. I’ll be following your blog!!

Thanks for your comments about hydrological impacts, Munir. They definitely show how environmental change has widespread effects. After reintroducing wolves in Yellowstone, researchers found that deer no longer browsed in the valleys and gorges because it wasn’t as safe as others areas. Vegetation in these areas began to regrow, solving some of the issues you’ve mentioned.

And you’re right that deer have a necessary ecological role, it’s just that we’ve allowed that role to grow out of proportion. But then again, maybe we should think about how wildlife has been negatively affected by the steep rise in human populations.

Thanks for your comments about hydrological impacts, Munir. They definitely show how environmental change has widespread effects. After reintroducing wolves in Yellowstone, researchers found that deer no longer browsed in the valleys and gorges because it wasn’t as safe as others areas. Vegetation in these areas began to regrow, solving some of the issues you’ve mentioned.

And you’re right that deer have a necessary ecological role, it’s just that we’ve allowed that role to grow out of proportion. But then again, maybe we should think about how wildlife has been negatively affected by the steep rise in human populations.