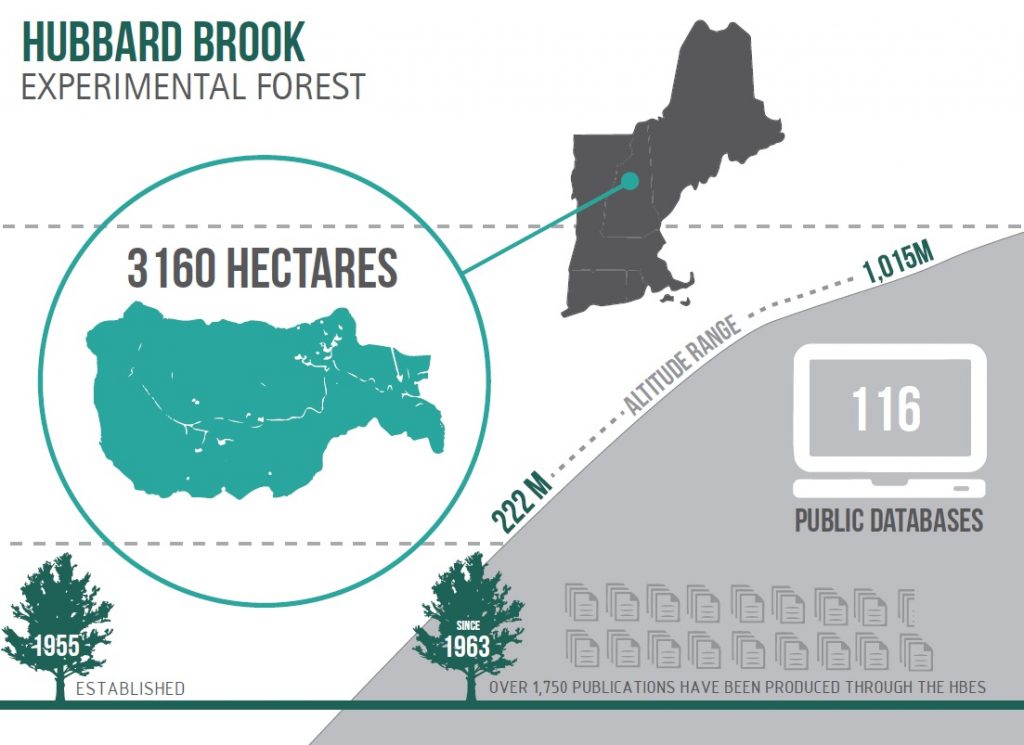

Many of my childhood memories are centered around the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, a Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) site in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. My mom has worked there for as long as I can remember, and during their summer meetings I would often tag along, swimming in Mirror Lake, hanging with my friends, babysitting the littler kids, or (when I got older) listening to the scientists present their research.

Because of my personal connection with the experimental forest, I have long known that its scientists discovered acid rain, that their datasets are as impressive as they are important, that walking through the forest plots can be like navigating through a maze of flags and markers. When I entered graduate school, I used Hubbard Brook data – which is free and available to the public – for landscape analysis and statistics projects.

Hubbard Brook is part of a country-wide network of LTER sites, in addition to a handful of international sites as well. Founded in 1980, the network “was created by the National Science Foundation (NSF)… to conduct research on ecological issues that can last decades and span huge geographical areas.” Think drought and precipitation experiments, climate change, large-scale disturbance. At Hubbard Brook for instance, they have recently created huge artificial ice storms to measure the impact of these freezing events on forest succession and many other ecosystem dynamics. The research is often done over large plots, and data recorded for years if not decades.

The network’s importance extends beyond its long-term projects. Many people picture “science” and “research” as activities occurring inside a lab, complete with technicians garbed in white coats and goggles. While obviously this is one facet of the discipline, the image is also not the complete picture. Scientists at Hubbard Brook and other LTER sites do much of their research out in the field, in all environments and weather conditions. For the ice storm experiment, participants used fire hoses to spray huge plumes of water into trees in the depths of a cold, winter night. Sure, the work is difficult, but it is also fun. People – especially students – should see this kind of environmental science.

As part of an effort to communicate about the LTER network, I’m taking my love for LTER sites on the road. In 2016 and 2017, my goal is to visit all 20+ sites in the continental United States, documenting their projects, people, and ecosystems. Stay tuned!