Welcome to my 3rd annual FEMMES blog post. FEMMES stands for Females Excelling More in Math, Engineering, and Science. It’s an undergraduate-led organization at Duke that provides STEM opportunities for local girls, notably with the annual Capstone event that occurred this past Saturday. Hundreds of girls in 4th-6th grade came to Duke’s campus for a day of STEM activities led by female professors, graduate students, and undergrads.

Lessons from the past

At last year’s FEMMES Capstone event, I quickly realized the activity I designed wasn’t hands-on enough. It engaged most of the girls and had them synthesizing information to reach a goal- but it was mostly on paper and lacked a “doing” component. This realization was sparked by a hard-to-please student in my first group of the day, who complained that she wanted to “make the green goop again like last year.”

In a similar event I volunteered for in college, the event organizers instructed us to make our activities as different from school as possible. That meant no powerpoints, no lectures, no worksheets, no passive learning. The activities had to make girls think critically, have them “doing” as much as possible, and provide opportunities they wouldn’t otherwise have at school.

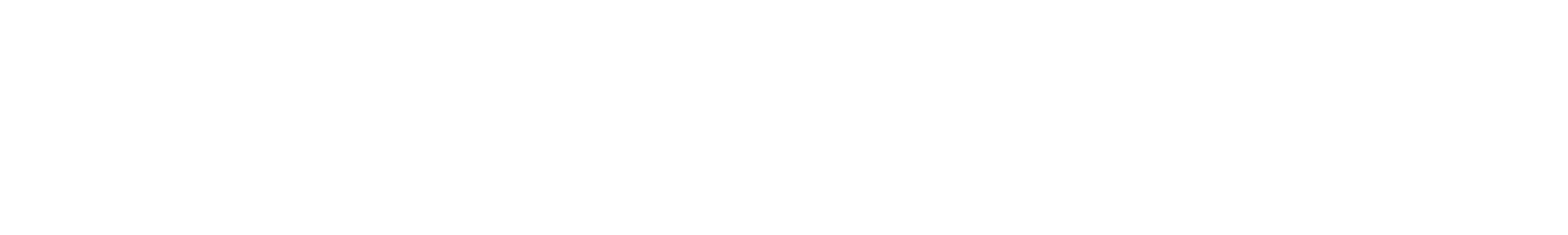

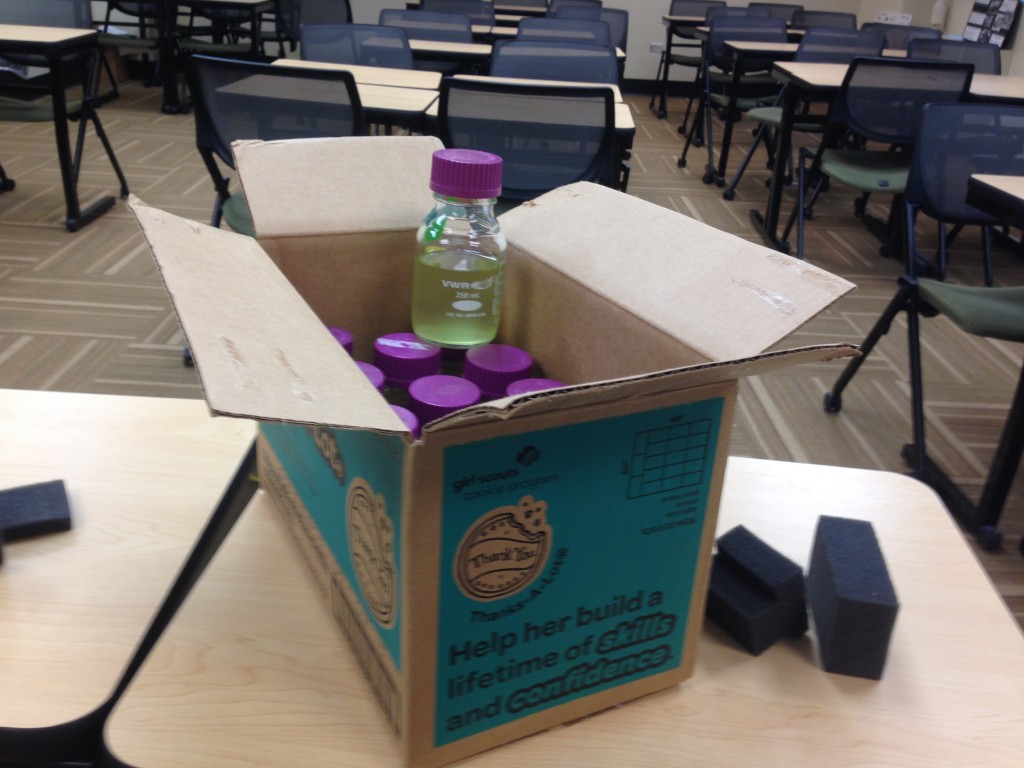

So, I vowed to make a more hands-on activity for this year’s event. For starters, there are an unlimited supply of pre-made activity plans easily found online. However, my research topic (algae growth for biofuels) and the activity time limit (45 minutes) narrowed down the options considerably. Moreover, online activities about algae are not very interesting: most involve growing algae cultures and adding extra fertilizer to one culture to see what happens. But, putting myself in the shoes of a 4th-grader, I reconsidered the interesting-ness of these kinds of activities. I decided to do the experiment activity, with some modifications.

The Activity

To get their minds warmed up to the topic of algae, first we talked about algae growth requirements and the students filled in a venn diagram comparing survival requirements for people and algae.

Next, they became managers of algae companies and were tasked with figuring out how to maximize algae production. Using the growth requirements they just learned about, they suggested ways to boost the growth of their hypothetical algae. They designed a simple experiment to test which might boost growth the most: adding extra nutrients, extra carbon dioxide, or extra light. Incorporating a quick lesson in experimental design, we talked about the need to have a control in the experiment. They also learned that, in reality, they would need to test many different levels of nutrients, carbon dioxide, and light- but for the sake of the activity we went with simplicity.

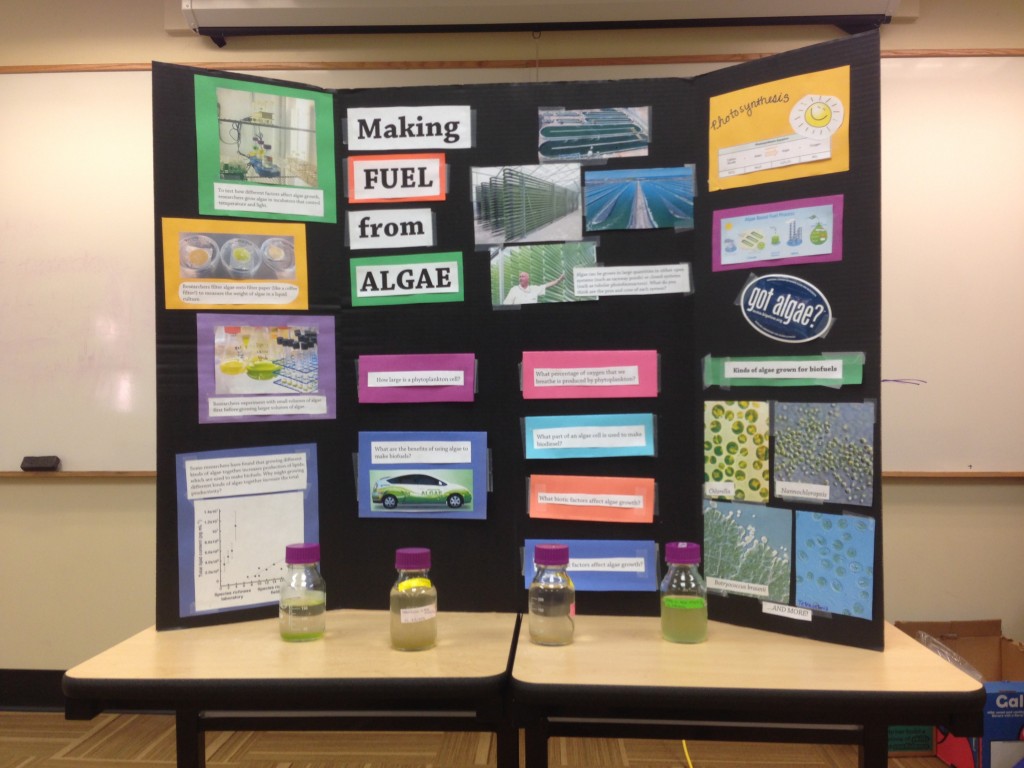

I brought everyday materials that I use in lab to grow algae, thinking it would be a good hands-on experience for them to go through the experimental set-up. They really enjoyed using the simple equipment such as plastic pipettes and tubing, and even divided up tasks amongst themselves so that everyone could try everything at least once.

First, they weighed out “nutrients” to make growth medium for their algae. I filled some glass jars with salt and sugar to represent nitrogen and phosphorus nutrients (they caught on to the contents’ real identity). I brought some plastic weigh boats and scoopulas from lab, and bought a kitchen scale for them to weigh the nutrients on.

Next, they applied the experimental treatments to their cultures. One culture was placed under a lamp or on the windowsill for extra light. Another group added extra “nitrogen” and “phosphorus” to their growth medium for extra nutrients, and another group attached an aquarium pump to their culture for extra air and carbon dioxide. Each group added a small amount of algae to their growth medium using plastic droppers.

However, since the algae would take a week to grow, I brought already-grown cultures with me and presented them as the experiment end-products.

We used a turbidimeter to measure the amount of algae in each of the experimental cultures. This handheld instrument measures turbidity, or how much “stuff” is in the water. It shines light through a water sample in a glass vial, and measures how much light can pass through to the other side. Algae were the “stuff” in our case, so the turbidimeter reading was proportional to the amount of algae in the sample. The girls eagerly peered over the turbidimeter screen, waiting for the number to pop up and tell them if their culture had the most algae.

They drew a graph on the whiteboard to compare results of the three experimental treatments and the control, reviewing which variables go on which axes of the graph. They were very motivated by the results because they viewed it like a competition, so perhaps I will integrate some kind of competition in next year’s activity. I had the girls compare the results to their predictions, and described how we could make the experiment better by having replicate cultures.

What I Learned

During the activity, everything I ever learned about scientific communication rang true. When I was a senior in college, Alan Alda visited my campus to talk about scientific communication. As an anology to what often happens when communicating with people outside your field, Alda had an audience member play a mystery song only by hitting a stick on a board. No one could guess the song because the stick couldn’t make different notes, it only had the beat. The audience member could hear the song in her head while playing (it seems so obvious if you do it yourself- tap out the song Happy Birthday on your desk), but it was in her own head and not being communicated clearly with the audience.

This happened to me many times throughout the day. I lived in a world of algae and microbiology, and the girls couldn’t always understand me when I stayed in that world and only used the beat stuck in my head, instead of using different “notes”. For example, while I was showing them my algae cultures I told them the scientific names of the algae strains. Someone asked me “Did you name it that?” I had assumed they knew that organisms had scientific names.

I did a better job of describing the experimental set-up and equipment to them, though. It made me wonder why we couldn’t talk in simpler language everyday in lab instead of using complex descriptions when there really wasn’t a need for them.

Above all, I embraced the girls’ curiosity and tried to get them thinking as much as possible. I answered all the “why” questions that never stopped (why does the algae look like that? why is there foam packed around the bottles? why does this stick to the bottom?), wanting to make sure they soaked everything in they wanted to know, even if it wasn’t directly related to my activity.

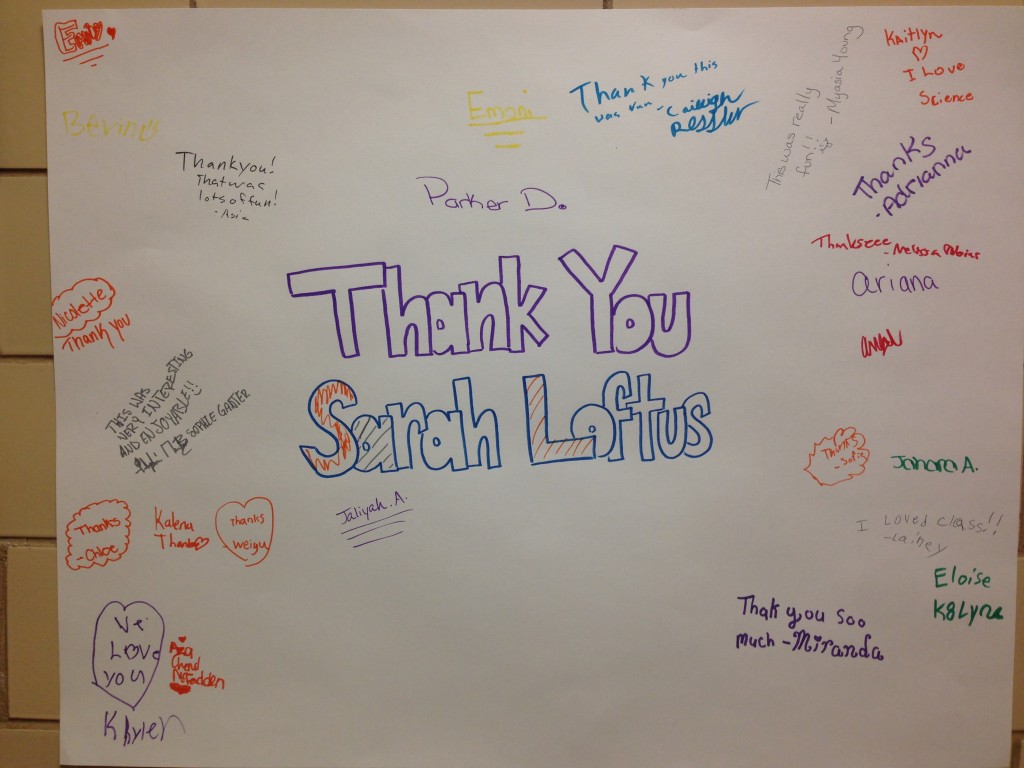

I led the activity four times througout the day, reaching about 27 girls in total. I think these direct connections with girls are what count. It was exhausting, but I am thriled to be part of an event like the FEMMES Capstone.