This article originally appeared in the Summer 2013 edition of Forest Notes magazine. The story, photos, and map are by Tripp Burwell. Christian Woodard contributed additional reporting.

This story is dedicated to Boyce Greer, who belonged to the Romaine more than most.

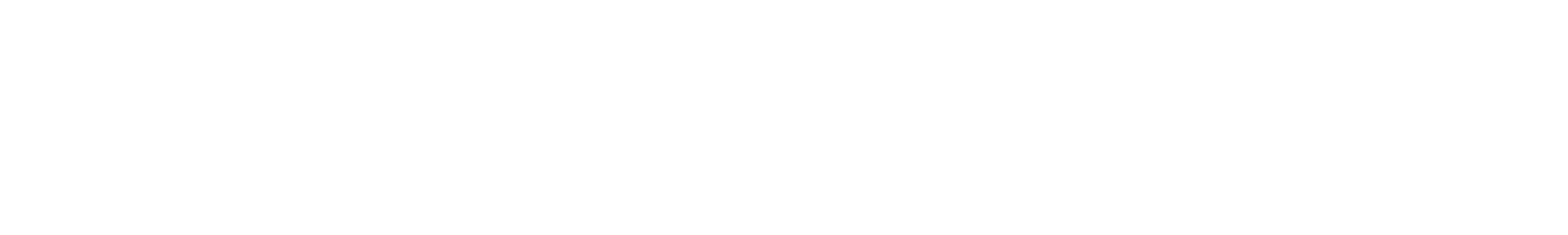

Dynamite blasts rippled the pre-dawn air as we paddled through the Romaine River’s cold, tannic water. Fog and black flies smothered the dense evergreen banks.

Three of us, Christian Woodard, James Duesenberry, and I had teamed up for the last descent of this huge and steep river.

For three days, we had paddled through the heart of the central Quebec wilderness. That night, we camped above Romaine 2, one of four Hydro Quebec dam sites—the future tombstones of a once free-flowing river.

A wall of gravel and boulders loomed downstream, diverting the flow into a tunnel punched through a nearby hill. We hoped to sneak through the construction and rejoin the Romaine wherever it returned to its ancient course.

The groan of hydraulic machinery lifting, drilling, and crushing stone joined rhythmic thumps of underground explosions. The air had the sharp, silicate smell of broken rock and blasting mixed with diesel exhaust.

As we floated closer, Duesenberry observed that our trip could be ending. Woodard countered that we would have a quick ride to the bottom.

Not as quickly as the new electricity Hydro Quebec hopes to sell to New England and New York, I thought.

ENGINES OF PROGRESS

Everybody, it seems, wants to “go green.” The states of the northeastern U.S. too have decided to power more of their energy consumption from sustainable sources—goals not lost on their provincial neighbors to the north. Quebec has mastered the art of turning flowing water into power, which many consider renewable.

In 1962, Quebec nationalized its major power corporation, Hydro Quebec. The company hauled the province into a modern economy.

New industrial jobs and affordable energy fostered economic independence and notions of self-rule in largely agrarian Quebec. By the early 1990s, 13 of the province’s 17 major river systems were transformed into engines of liberation and progress.

North and east of Quebec City, the capital, the north coast of the St. Lawrence River tilts sharply into its gulf. Powerful rivers spill over steep granite, pounding hundreds of miles down to the sea.

The Côte-du-Nord is a goldmine of energy potential. Its rivers are also perfect settings for challenging multi-day whitewater trips.

First paddled in its entirety solely for its whitewater in the 1980’s, the rapids, wilderness experience, and impending damming afforded legendary status to the Romaine in the whitewater community.

During a previous trip, Woodard learned that Hydro-Quebec planned to begin turning the Romaine’s gorges into reservoirs in late 2010. By spring of 2011, they were a year behind schedule.

Three teams had paddled it before us in 2011, the busiest whitewater summer for the Romaine. We were the last trip of the last season; this was the last chance that anyone would ever have to kayak it.

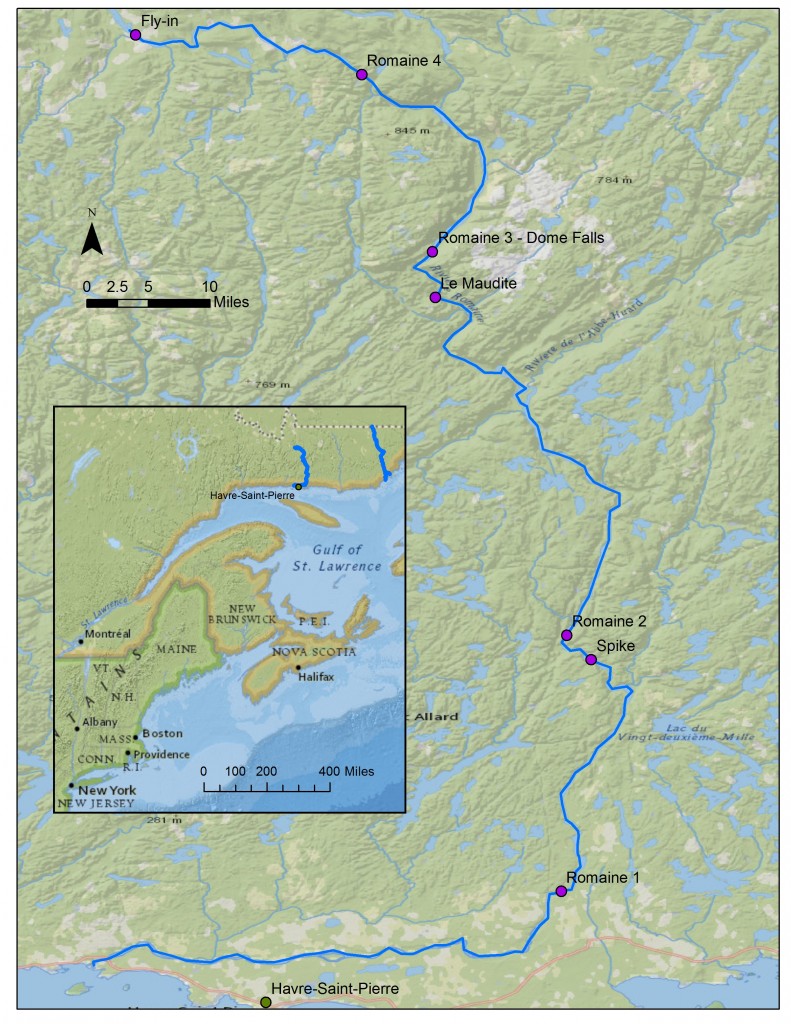

To get to the Romaine 2 dam site, where we hoped to bypass the construction to continue our trip, we had flown 125 miles into the bush from Havre-St-Pierre and paddled 75 miles of river.

While stuffing gear into boats at the floatplane base, one of the pilots had warned us that Hydro Quebec had been removing paddling groups above the dam and transporting them back to Havre-St-Pierre.

With no plan except a burning desire to run the whole river, we had flown in anyhow.

QUEBEC’S ENERGY FUTURE

The Romaine Complex is part of Plan Nord (also known as Le Nord pour tous, or “The North for All”), a new energy, mining, and development initiative for northern Quebec.

Announcing the plan in May of 2011, Premier Jean Charest called it “the most important sustainable development project for the future of Quebec.”

Plan Nord includes three major dam construction projects, the Eastmain 1-A/Sarcelle/Rupert (920 MW – megawatts), the Romaine (1,550 MW), and the Petit Mecatina (1,200 MW).

Hydro Quebec finished flooding the Rupert River in 2010, began construction on the Romaine in 2009, and intends to start on the Petit Mecatina River in 2015.

Only two of Quebec’s 17 major river systems will remain untouched. Flooded forests in the sparsely populated north will provide a power platform for widespread development, both in Quebec and the Northeast.

The two main political parties in Quebec, the Liberals and the Parti Québécois, both support this ambitious project to open the north to mining and other resource extraction.

Quebec’s defining political issue is whether Quebec should become independent of Canada. Premier Charest’s Liberal Government, which favors staying in Canada’s federal system and traditionally supports big business, introduced Plan Nord.

Parti Québécois’s mission is Quebec sovereignty. The party believes that Hydro Quebec should do what it has always done—push Quebec towards independence.

SELLING ELECTRICITY AT HALF COST

As Plan Nord ventures deeper into Quebec’s geographic margins, Hydro Quebec pushes farther into its profit margins.

Hydro Quebec expects the fully-completed Romaine Complex will cost $6.5 billion plus another $1.5 billion to build power lines to the United States.

According to Hydro Quebec’s impact assessment, power produced from the Romaine will cost 9.2 cents per kWh (kilowatt-hour), about 40 times as much as the massive Churchill Falls hydroproject in neighboring Labrador.

Any dam on the Petit Mecatina, which has neither a road nor a town at its mouth, would only be more costly.

Hydro Quebec has committed to sell power from the Romaine Complex to provincial aluminum smelters at 4.2 cents per kWh and to Vermont at 5-6 cents per kWh, approximately half of the generation cost.

When asked about the price gap, Hydro Quebec referred all media requests to the Quebec Ministry of Natural Resources. Nicolas Bagin, a spokesman for the Ministry, commented that Hydro Quebec “does not sell power to the U.S. at below generation costs.”

Opponents say otherwise, surmising that since Hydro Quebec is nationalized, increasing electricity bills for Quebecois will cover the loss in government revenue for selling electricity at half-cost.

A VISION FOR THE NORTHEAST

So far, Vermont is the only state with a power contract for electricity from Hydro-Quebec’s portfolio of dams and power plants.

Vermont citizens and Gov. Peter Shumlin have long campaigned to replace the output of the Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant, the state’s largest energy provider, with green power.

Three years ago, the Vermont Legislature expanded the definition of renewable hydro power. Previously, only projects generating less than 200 MW fit that designation; now all hydro projects qualify, including those under Plan Nord.

Vermont will save its vistas at the expense of pristine forests in Quebec, rather than promoting local solutions to its energy issues.

Hydro Quebec’s U.S. plans do not stop with Vermont.

In partnership with Northeast Utilities, Hydro-Quebec wants to construct the “Northern Pass,” 180 miles of high-voltage power lines, to transmit 1200 MW through northern New Hampshire into the lucrative southern New England market.

In New York, Transmission Developers, Inc. (TDI) plans to implement the Champlain Hudson Power Express, bringing 1000 MW of hydropower from the Canadian

border to Queens.

As TDI CEO Donald Jessome said on the Journal News’ Editorial Spotlight, “These generators … are being built as we speak …this is a great opportunity to get access to a resource that’s being developed and looking for a market.”

Connecticut is currently considering a change in legislation similar to Vermont, designating any hydropower from Canada as renewable.

Only some Northeasterners share Hydo-Quebec’s vision.

In New Hampshire, the Society for the Protection of N.H. Forests and its conservation partners are fighting Northern Pass’s initial proposal for an above-ground transmission line bisecting the state, arguing that the transmission line would mar the landscape, harm the state’s important tourism industry and erode property values, all for corporate gain and little public benefit.

Challengers of the Champlain Hudson Power Express counter that New York currently has ample supply and that infrastructure issues pose a greater problem for the state’s grid.

“What’s the rush for new energy?” asks Paul Messerschmidt, an energy consultant who has worked for the Cree Indians in Quebec.

“In 2013, we have lots of surplus capacity in both the Northeastern U.S. and Southeastern Canada. There is currently no need for new capacity, and little, if any, in the next 10 years. Even if there were, natural gas is abundant, cheap, and will be for years.”

THE SOCIAL COST

The Romaine Complex’s unnecessary new capacity comes at significant social cost for Quebec’s Innu peoples, who have called the Romaine and its forests home for a thousand years.

Innu poet Rita Mestokosho said, “I am convinced that making a dam north of our land will destroy a lot of dreams. It will destroy our culture, our language, Innu-aimun. It will destroy our medicinal plants, it will poison the animals, it will pollute the air we breathe.”

At a meeting with Hydro Quebec representatives in her village of Ekuanitshit (Innu-aimun for “take care of the place where you live”), Hydro Quebec employees told Rita and other village leaders that power lines would go through their lands whether or not they signed an agreement with the utility.

Feeling they had no choice, Ekuanitshit signed to receive what they could out of the deal.

As Rita later explained to me, “The dam project has always existed in the minds of engineers at Hydro-Quebec. They are waiting for the right moment to create division within the Innu Nation, and even within our community.”

Many other towns have signed agreements to allow power lines on their land; only Uashat-Maliotenam has held out so far. In the spring of 2010, Hydro Quebec proposed routing power lines through the village and offered $4 million in compensation.

Uashat-Maliotenam refused and the governing Band Council sought an injunction against the Romaine power line project.

In the fall of 2011, Hydro Quebec returned with more money, but again the village refused. The situation is currently in court, even though dam construction continues.

This treatment of First Nations is standard behavior for Hydro-Quebec. In the 1970s, the corporation flooded 4,440 square more miles of Cree and Inuit hunting grounds to build the La Grande Complex (1.5 cents per KWH, 15% of the cost of Romaine power), without consulting the communities beforehand.

In 1975, both sides signed the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement that provided $225 million in compensation for flooding 350,000 square miles of Cree and Inuit lands.

Boyce Richardson, who wrote the definitive account of the Cree and Hydro Quebec in his book, Strangers Devour the Land, remembers that the “Cree were under a lot of pressure to make an agreement.

“Either they signed it and got something or they didn’t and got a project around their neck, because it was already started.”

Despite the contract, the Crees have had to go to court to make sure almost every part of the agreement was honored. For the Rupert project, the first 920 MW of Plan Nord, Hydro Quebec again promised to honor the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, but offered no new compensation.

INEFFECTIVE RESISTANCE

Though First Nations have received economic compensation for their ancestral lands, the cultural result has been a glacial assimilation into Western society. Many semi-nomadic hunting families were pooled and diverted to government-designed towns where they then sought wage employment to pay for their amenities.

Richardson feels that “the Crees have fought less as they have become more integrated … [however,] they have made a fairly successful integration, as best they could.”

“As best they could” may have left both the Crees and the Innu in cultural limbo – too far removed from the land to fight passionately about it, but also too far removed from the mechanisms of Quebec society to fight effectively for it.

Chris Scott, spokesperson for Alliance Romaine, a Quebec non-profit, remains hopeful that growing awareness and political activism, particularly among the Innu along the Côte-du-Nord, will result in the Cree and Innu reclaiming more ownership of their future.

“It’s not over until all the dams are built,” said Scott.

Meanwhile, Hydro Quebec labors on.

Sam Howe Verhovek, who has written about Hydro-Quebec for the New York Times Magazine, told me, “Hydro Quebec, as an entity, is hugely confident in what it does. They think they’re doing the Lord’s work.”

‘WHILE I STILL COULD’

Woodard and I had decided before climbing into the plane that we would portage Le Maudite.

Translating roughly to “The Devil,” the rapid spreads over a series of angled shelves, creating chaotic waves at the top of the chute and finishing with two big holes at the bottom.

Recirculating features of that size can stop a paddler and hold them for several minutes.

But knowing that once built, Romaine 3 will turn Le Maudite into a placid lakebed, Duesenberry had decided to fire it up. The width and power of the river dictated that he would be alone, amidst a giant series of turbulent, crashing waves.

He thought that he would be able to make it through the rapid, but he could not see exactly how.

Woodard launched into the pool below the rapid, offering token clean-up support in the darkening evening.

A very small Duesenberry ferried out in to the center of the river, angling left through the first drop, dropping awkwardly into the second. He flipped, rolled, and flipped again while sliding down the third.

In the fourth, he fought his way out of both holes, tweaking his shoulder. Woodard, though glad to see him upright at the bottom, remarked that it had not looked smooth.

Duesenberry replied, “No, but it’s the last time anybody will run it. It was something I needed to do while I still could.”

The opportunity to be the last to do anything exerts an irresistible pull to many who play and work in the wilderness.

By damming the Romaine and the Petit Mecatina, Hydro Quebec would essentially close their hydropower frontier.

This may have led to myopic decision-making on their part, offering cures for which there is no disease and ignoring other possible solutions for

a truly green energy future.

What happens when Hydro Quebec dams the last wild rivers in the province?

Messerschmidt lays out an alternate vision to the continued damming of Quebec’s major rivers. “The optimal strategy for Quebec would be to develop their wind resources (estimated at over 15 gigawatts) to work in conjunction with their existing hydro resources, which would serve as storage for intermittent wind resources.”

He notes that expanding wind capacity is far cheaper than building new dams.

“It’s a mystery why they keep throwing up dams,” Richardson said.

A BLIND EYE

Dawn at the Romaine 2 dam site eased into morning. The blasting quieted down and banks of halogens flicked off down the riverbed. We shouldered our boats and walked over the rocky fill, hoping to look purposeful.

Around the corner, we were shocked to see the river returned to its ancient course. Instead of flowing through turbines at the end of a dry canyon, it was diverted for only a few hundred yards.

We could keep paddling if Hydro Quebec did not stop us.

On a higher road a man stepped out of a modular building and pointed at us.

Another joined him, and they walked to a pickup truck. Two other men leaned on a backhoe, drinking coffee.

“Bonjour,” Woodard said.

They both nodded and turned away.

Taking an “if we build it, they will come approach,” Hydro Quebec has ignored First Nations, energy economics, and actual renewable solutions to finish damming the rivers in Quebec.

Many in the Northeastern U.S. have been happy to follow their lead.

As Hydro Quebec turned a blind eye to us, like so many others, we slid back into the water under the redoubled cacophony of construction.

——

Editor’s note: The Romaine Complex 2 dam is still under construction.

The company’s website indicates the first of the four Romaine

River dams will be commissioned sometime next year, and the full

project is slated to be completed by 2020.