Finally, the dust from the 2018 midterm election has settled. The general wisdom is that the returns were mixed for proponents of environmental and climate change policy. Here are a few key takeaways:

- The House has flipped to Democratic control, allowing the opposition party new oversight powers over the Trump administration. This includes the under-appreciated power of approving federal budgets and appropriations (Imagine the House barring the EPA from using its funds for regulatory rollbacks).

- The Senate has become (slightly) redder, enabling the President to appoint more far-right cabinet members and judges without fear of a confirmation battle. Case in point: Andrew Wheeler, the former coal lobbyist who took over the EPA after Scott Pruitt’s less-than-graceful exit, will be tapped to lead the agency permanently.

- Environmental ballot initiatives were drowned out by big spending from Big Oil and friends. Most disappointingly, Washington’s carbon tax initiative I-1631 (which I wrote about last month) failed to overcome fossil-fuel-funded negative ads and convince voters that pricing pollution was a good idea.

- More encouragingly, state governments are poised to take a stronger lead on environmental policymaking. Several state legislatures saw at least one chamber turn blue. And seven states will be welcoming Democrats, most of whom are also climate and clean energy champions, into their governors’ mansions for the first time in four or more years.

From my point of view, this last development may be the biggest reason for optimism going into 2019—potentially overwhelming the “mixed results” narrative of the election by paving the way for more ambitious environmental policies in more states. In at least five cases, new governors-elect have committed to join the nation’s premier group for climate-fighting states: the U.S. Climate Alliance.

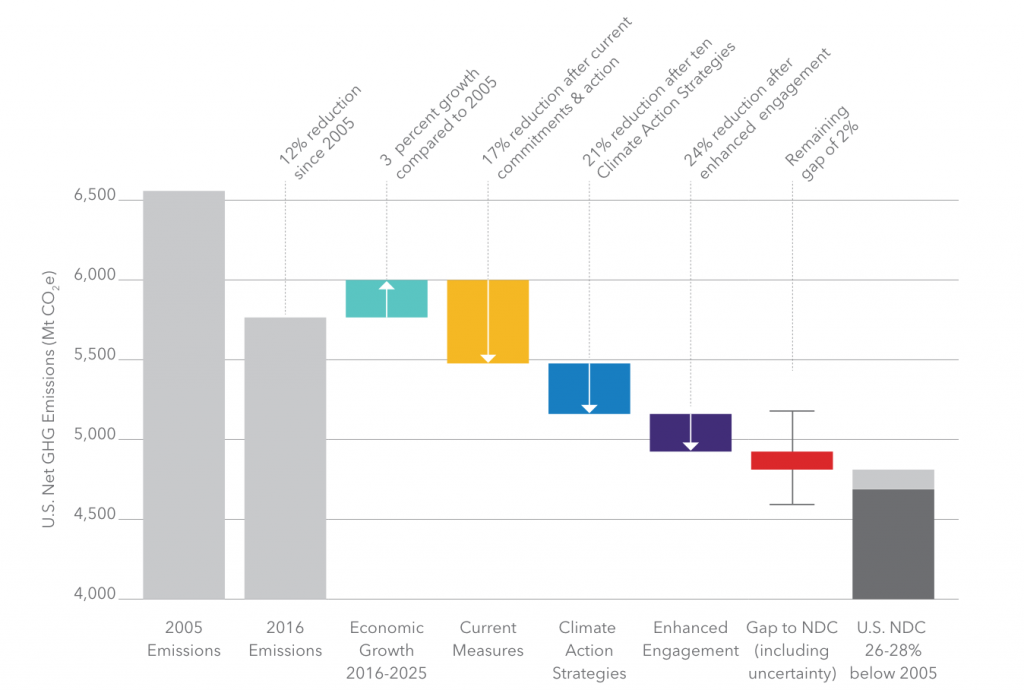

Formed on June 1, 2017, the same day that President Trump vowed to pull the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement on climate change, the alliance represents a bipartisan group of governors committed to upholding the Paris Agreement within their states. These states plan to keep their end of the bargain in realizing President Obama’s pledge to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by 26-28 percent in 2025, even if the rest of the country falls short.

Now, the 17 states that have joined the U.S. Climate Alliance are beginning to take real policy action. In California, Gov. Jerry Brown enacted the Cooling Act, which adopts strict standards on the use of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), one of the most potent greenhouse gases, and provides incentives for the use of alternative coolants. New York, Maryland and Connecticut have already promised to take similar steps. In North Carolina, meanwhile, Gov. Roy Cooper recently issued an executive order targeting a more ambitious reduction of 40 percent of greenhouse gases by 2025. The order also pledges to put 80,000 electric vehicles on the road by 2025.

The midterm election has now paved the way for the Alliance to expand its reach from the coasts into the Midwest and Intermountain West. These new additions will greatly expand the Alliance’s geographic diversity: as it stands, only Colorado, Minnesota and Vermont don’t border an ocean.

The expected U.S. Climate Alliance class of 2019 includes:

Michigan, where incoming governor Gretchen Whitmer has tied climate change to lowering water tables and stimulating algal blooms. As the seat of America’s auto industry, which is now responsible for the largest wedge of greenhouse gas emissions nationally, Michigan’s participation in the alliance is a huge opportunity for action on transportation.

Wisconsin, where Republican Gov. Scott Walker lost his seat to Tony Evers. In addition to committing his state to upholding the Paris Agreement, Evers hopes that environmental stewardship will translate to new jobs in forestry and small-scale agriculture.

Illinois, where incoming governor J.B. Pritzker has promised to put his state on a path to 100 percent clean, renewable energy. That will be no small feat for the third-largest coal-producing state in the country, which last year produced nearly one-third of its power from the dirtiest fossil fuel.

Nevada, where governor-elect Steve Sisolak plans to get his state to 50 percent renewable energy by 2030, and on a path to 100 percent thereafter. Nevada has the most solar power potential of any state in the U.S., but barely cracked the top 10 for new solar installations last year—meaning Sisolak will have lots of room to grow his state’s clean energy industry.

New Mexico, where incoming governor Michelle Lujan Grisham has also joined the call for 50 percent renewable energy by 2030, and has also promised to crack down on methane leaks from oil and gas fields. New Mexico’s loosely-regulated oil and gas industry was responsible for producing the largest methane cloud in the country—so Grisham’s clean energy agenda could not come at a better time.

In addition to those five states, the alliance may find willing partners moving into other governors’ mansions. In Maine, governor-elect Janet Mills has sued Scott Pruitt’s EPA over its rollback of the Clean Power Plan, and now proposes an ambitious goal to cut Maine’s (already tiny) greenhouse gas footprint 80 percent by 2030. And in deep-red Kansas, Democratic governor-elect Laura Kelly’s promises to address water quality and work with agribusiness could present opportunities to work with alliance states on carbon-friendly agriculture.

So what does this new membership drive mean for the alliance? Right now, these states make up about a quarter of the U.S.’s total greenhouse gas emissions. If all the states mentioned above join through their new Democratic governors, the share of U.S. emissions covered by the alliance would rise to 37 percent—increasing its potential for impact by half. That’s largely thanks to Illinois and Michigan, which both rank in the top 10-emitting states. Getting them onboard for ambitious climate action is a big deal.

Just how big of a deal, you ask? My current organization, the World Resources Institute, contributed to a recent analysis of how far the U.S. can get toward the greenhouse gas goals Obama set under the Paris agreement, solely through state and local actions. Those actions, which include the current efforts of the alliance, could reduce US emissions 17 percent by 2025, the study found. (Remember, our national goal is 26-28 percent by the same year.) But with more ambitious climate action strategies, states and other subnational actors could achieve a reduction of 21 percent by 2025. And with enhanced engagement by more states, cities and companies, the national emission reduction could reach 24 percent, just 2 percent shy of Obama’s goal.

That’s why expanding the U.S. Climate Alliance is so critical. The more states that are engaged in upholding the Paris Agreement and pursuing climate action strategies tailored to local needs, the closer we as a country can get to honoring our pledge made in Paris to every other country on Earth—without relying on this president to get us there. And that is a New Year’s resolution for 2019 we can all get behind.