We know human activities lead to a lot of untimely bird death and are causing an acceleration in extinction rates. In this series of posts, “Killing Birds,” I examine the mechanics of anthropogenic bird death. How are we killing these feathered creatures that we, oh, so love?

Last time around we covered threat #1: the domestic cat (2.4 billion birds per year in the US). Here we discuss the runner-up: collisions with windows, which are estimated to kill about 1 billion birds per year.

Since we’re throwing around these incomprehensibly large numbers, let’s try to make an effort to put them into perspective. The United States wild bird population was estimated at 20 billion birds by the American Ornithologists Union in 1975. So if we combine the estimated impacts of cats and birds, we’re talking about an annual culling of 17% of US birds. That’s a serious conservation problem!

Fortunately bird-window collisions have been getting some attention in the media lately. The Minnesota Vikings have been publicly criticized for not embracing bird-friendly design in their new football stadium and the State of New York just launched a ‘lights out program’ last month to help mitigate deaths of birds migrating through the Empire State. More and more organizations are becoming aware of bird-window collisions and deciding to take action to prevent them.

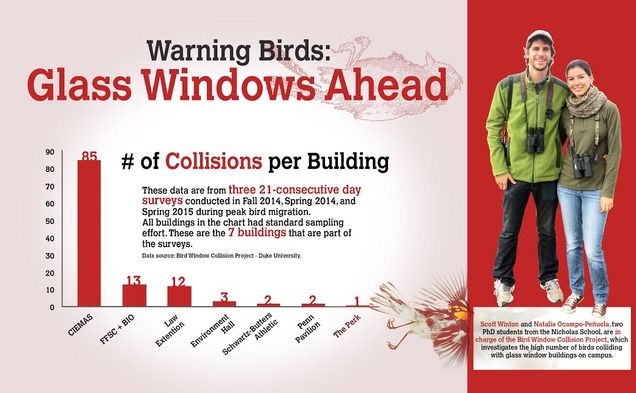

The effort to prevent bird window collisions at Duke, which Nicholas School PhD candidate, Natalia Ocampo-Penuela, has been leading, received coverage from The Chronicle last week. To my surprise, it then was picked up by local TV News Station WNCN, which interviewed Natalia and Nicholas School instructor Nicolette Cagle on camera. Have a look!

While these news stories may portray a crisis or “black eye” for Duke, I only see a golden opportunity. A few cities, such as Toronto, Chicago and San Francisco have emerged as early proponents of bird-friendly architecture and lighting, but as of yet, there are no ‘bird-friendly’ colleges and universities in the US. Duke is uniquely poised to be the first. Thanks to the efforts of student and staff volunteers, it has background data on collisions for several buildings. We know that the engineering building, CIEMAS, poses the biggest threat. If Duke can manage to retrofit CIEMAS and implement some best-practices for its many pending glass-heavy construction projects, it can make a strong case for being #1 in bird friendly design, rather than #1 in bird death.

I wrote a resolution asking the Duke administration to pursue bird-friendly actions a couple months ago. The Graduate and Professional Student Council, which represents more than 8000 students, passed it unanimously. Since then, bird-window collisions has been part of the agenda of the Duke Facilities and Environment Committee, so I’m optimistic we will see some tangible action for the sake of birds on Duke’s campus soon.