The “two revolutions” projected at the end of my last post are expanded here to “three revolutions”. These are major transformations that bear emphasizing among a large number of significant changes over time in how humans have looked at the Universe they occupy.

My objective is to move from a view in which the technosphere is assumed to be an entity built and maintained by the purposeful actions of humans, to consideration of the technosphere as a natural phenomenon that emerged from the Earth without an intelligent designer, human or otherwise.

This is not to say that the combination of human agency and intelligence is not an indispensable component of the technosphere. It is. But this property is not a human property, just as in the hydrosphere the collective property of wetness is not a molecular property.

This is not to say that the combination of human agency and intelligence is not an indispensable component of the technosphere. It is. But this property is not a human property, just as in the hydrosphere the collective property of wetness is not a molecular property. Here I argue that the effect of collective agency in the technosphere is best thought of not in terms of a “designer”, but as an emergent quality that should be treated on its own merits.

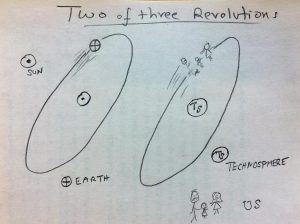

This transformation or change of perspective can be thought of as the historical product of three revolutions, i.e., three fundamental changes in how we look at our place in the world. The first of these was the Copernican revolution, sparked by the publication of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium by Polish astronomer and polymath Nicolaus Copernicus in the 16th century. Copernicus argued that the Earth was not the center of the Universe about which the Sun circled, but occupied a more subordinate position, the Earth orbiting instead around the Sun. The Earth became just one more object in a spectrum of planets, moons, comets, and falling stars. By extension humans were also demoted to a peripheral position, raising doubt about their primacy in the order of things.

The second revolution in this transformative process was spurred by Charles Darwin’s publication of On the Origin of Species in the middle of the 19th century. Darwin introduced natural selection as a key mechanism for explaining how biological species, including Man, could arise by natural processes without the aid of a plan or a designer.

This development was in some ways a stronger blow against the centrality of humans in the Universe than the world view introduced by Copernicus….. Evolution was more personal.

This development was in some ways a stronger blow against the centrality of humans in the Universe than the world view introduced by Copernicus, which could seem like an argument about distant astronomical niceties. Evolution was more personal. After all, it was easy to compare the assumed august status of humans with that of apes, and see that according to Darwin they were not so different.

So the Copernican revolution de-centered Man from the focal point of the Universe, but apparently left him alone and at home on an Earth that for all anyone knew was made expressly for him. But then Darwin appeared and further de-centered Man, this time from the pinnacle of biological creation. Instead, happenstance in the form of variation guided by the impersonal forces of selection tended over time to produce organisms of great variety and complexity, including us. And no designer was needed.

However, a still closer approach to a planet of scientific understanding can be achieved by one more revolution in the human world view: an Anthropocene Revolution that further de-centers humans from the central position they are often assumed to occupy as prime architects of the Anthropocene world, i.e., as the designers of the technosphere. Here I take a cue from history to ask, again, if a world-designer is really necessary.

This is just an appeal to take a non-anthropocentric stance that makes no a priori assumption about the human role in the evolution of the Earth, and then from this stance to consider the condition of humans as parts of the technosphere.

This is just an appeal to take a non-anthropocentric stance that makes no a priori assumption about the human role in the evolution of the Earth, and then from this stance to consider the condition of humans as parts of the technosphere. This approach leads to a final de-centering of humans from the prime authorship of the modern world, placing them instead as one among many authors, or (if one likes) causes.

Of course there is no argument that humans are not essential elements of the Anthropocene. They are essential. Without them there would be no technosphere. Nor is there an argument that human intentions and beliefs are unimportant in addressing the challenges of the Anthropocene. These human factors are critical. But nonetheless, as I will argue, the assumption that humans are the creators of technology and society leads to a one-sided and incomplete description of the technosphere and hence the Anthropocene.

Instead, I try to contribute to a planet of scientific understanding, as it appears to me, by analyzing the technosphere as a geological phenomenon, i.e., just the next new thing that the Earth is doing in its long history of change.

Instead, I try to contribute to a planet of scientific understanding, as it appears to me, by analyzing the technosphere as a geological phenomenon, i.e., just the next new thing that the Earth is doing in its long history of change. To me, this non-anthropocentric approach represents the least biased starting point for analyzing the world we humans confront every day.

Persistent citation for this post: P. K. Haff, 2.5 Three revolutions, in Being Human in the Anthropocene blog, 2018. https://perma.cc/KB97-EUKV.

This is the final post to 2.0 The Anthropocene, the second “chapter” of Being Human in the Anthropocene. The next post, 3.1 What I mean by a system, begins chapter 3.0 Being a system.

… I think what Carsten is hinting at, Peter (if I may), is that we’d very much welcome an article on your approach to these matters, for Cultural Science Journal, which is now at https://culturalscience.org/ (without the hyphen). Please consider!

Hi John. Thanks for the thought. My blog seems to be wiping out an inordinate amount of time, and I have a queue of projects that are awaiting attention. But I’ll keep CSJ in mind in case the right idea comes along. Peter

I fully agree! Perhaps the simplest way to express this third evolution is that we need a non-anthropocentric theory of meaning. That is, after Darwin we still think that we are in charge of our thinking. But thought is nothing that happens without media of thought, such as now, my writing, using the computer, the internet and so forth. There are scholars in the humanities field that start to work on that, like my friend John Hartley (see the book: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/cultural-science-9781849666022/). I am a member of a group of scholars who launched this new field, ‘Cultural Science’, in 2008. There is a journal devoted to that: http://www.cultural-science.org/

What happens here is to suggest that culture is a materialistic phenomenon, and our thinking is reflecting the evolution of culture,, which is itself embodied in artefacts. It is straightforward to include this approach in a theory of the technosphere, as you envisage it. The cultural science initiative will be relaunched this year, and in the new inaugural issue of the journal I will have a paper on ‘Darwin and Dilthey Combined’.

Thanks for the pointer to cultural science initiative.

A physical perspective can provide the non-anthropocentric vantage point we really need to fully appreciate the human condition in the Anthropocene, including especially that “humans-plus-technology” (including media, as you say) is not the same thing as “humans”. It is on the contrary often adversarial toward humans.