Day three on Midway Atoll- tour by bike and digging in the dirt

To say the role of resource managers on Midway Atoll is challenging is an understatement. In a place as geographically isolated and as biologically and historically rich as Midway Atoll, preserving natural and cultural resources and pleasing the people who care about those resources is no easy task. We spent day three on Sand Island learning about the Island’s resources as we toured around by bike, reintroduced bunch grass and removed invasive species, and (two of us) accompanied NMFS biologist Tracy Wurth on a Hawaiian Monk Seal population survey.

I think it is fair to say that as Coastal Environmental Management students, it was the biology and natural history that drew (most of us) to this amazing atoll. However, once you look past the tremendous physical beauty and the ridiculous number of albatrosses, you begin to understand and appreciate Midway Atoll’s role in US history and the human legacy that has shaped the environment of these islands. After the first recorded human landing on Midway Atoll in 1859, the physical transformation of these islands began. The US Navy significantly altered the landscape of Sand Island by dredging a channel through the reef and depositing the fill, resulting in an expansion of the island and the changing of water circulation patterns within the atoll.

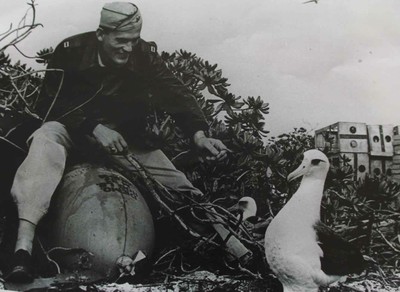

Over the years Midway Atoll has functioned as a station for a national cable company, a luxurious destination for the privileged and well-traveled guests of Pan Am, and most notably, the scene of the Battle of Midway between the US and Japan. Each change in use brought with it a new look for the islands. Ironwood trees were planted, barracks were erected and later bombed, and open space was paved for runways, all in the name of progress. When the Navy transferred authority of the Atoll to US Fish and Wildlife Service, it also handed over contaminated sand and soil, hidden garbage dumps, dilapidated buildings, invasive species, and the daunting task of preserving and protecting numerous threatened and endangered species.

Addressing these threats to the ecosystem is a continuous battle (as we learned today while pulling the dreaded verbensina plant), but it is reassuring to know that there are victories along the way. The Laysan duck is a perfect example of a conservation success story- a translocation project that worked. The cooperation of USGS and USFWS brought back the Laysan duck population from 11 recorded individuals in the 1930s on Laysan Island to populations in the hundreds on Laysan, Eastern, and Sand islands. The successful translocation of this species required providing a freshwater source in the form of seeps (small ponds that access groundwater) and adaptive management to combat new threats as they emerged, such as botulism from stagnant seeps.

It is reassuring to know that human manipulation of the environment can have positive results, as history has shown us is not typically the case.