Our jeep rumbled rumbled past a mother rhino and calf in the tall grass. It was great to see another rhino. But where were the tigers?

I thought I had glimpsed the orange and black stripes a little ways past – but how many times had I thought that already and been wrong?

Soon, however, other jeeps behind us slowed down and clogged up the one lane dirt road.

Riders and drivers alike began pointing, gesturing, their voices gathering and rising like a steady drumbeat. Tiger, tiger, tiger.

My friend Kamal beat the top of our jeep – “Bas. Bas. Bas.” he told the driver (stop in Hindi). Kamal and I both really wanted to see tigers too.

I was concerned though. The mother rhino and calf had been awfully close to the road.

The driver reversed the hundred yards or so toward the growing tiger jam (a traffic jam caused by tiger viewing).

And then the mother rhino stuck her head out in the road between us and the tiger jam.

Kamal started yelling “Chelo! Chelo! Chelo!” (“Let’s go!”)

The rhino was quick though. It was getting up to speed before our driver could put the car in gear.

I involuntary slid to the front of the jeep. The driver finally got the car in gear. The rhino kept coming.

I had been mock charged by rhinos before in Namibia – this rhino was definitely not mock charging.

I felt we couldn’t move fast enough.

Finally, the driver created space between us and the rhino before we ran into more tiger traffic.

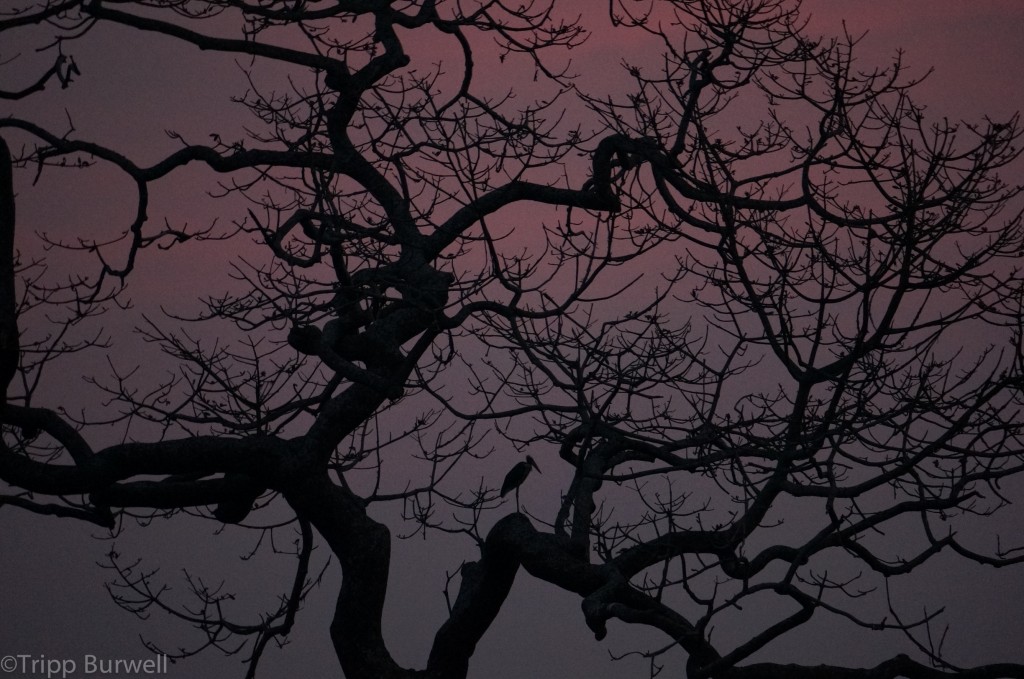

We were in Kaziranga National Park, in north-east India, famous as the last stronghold of the Assamese one-horned rhino (90% of the world’s population lives in the park).

There are rhinos all over the place there. In the park, outside the park, on the park boundaries.

It’s clearly been a successful effort in fortress style conservation – walling something off and keeping humans from damaging it too much.

Kaziranga has severely cracked down on poaching as part of this effort, which is a major problem in other parks nearby.

Some of their efforts have been controversial. Last year alone Kaziranga officers killed 22 poachers.

Poachers killed a similar number of rhinos.

On the other side of the viewing/use divide, we had been lucky to not be caught in the tiger jam when the rhino charged.

The traffic in Kaziranga reminded me of bear jams that I used to see when I worked in Yellowstone.

Battling poaching and managing tiger jams requires park resources – a lot of staff time and communication.

Two friends of mine published a paper last year on the economics of roadside bear viewing.

They found that visitors would be willing to pay about “$41 more in Park entrance fees to ensure that bears are allowed to remain along roads within [Yellowstone National] Park.”

Another recently published paper. “Valuing access to protected areas in Nepal” demonstrated that visitor’s mean willingness-to-pay in park fees to visit Chitwan National Park is over 2.5 times the current fee. Increasing the park fee to that amount would add 80% to the park’s revenue.

This seems to be the new direction of many protected areas.

Where they can, they arm themselves heavily against poachers.

One option, it seems, to pay for that increased staff time is to increase fees where people are willing to pay them.

What would you pay to see these animals? How much does their existence mean to you?

Does your willingness to pay match the current estimate of $850 for a pound of ivory in China?

If elephant tusks usually produce about 22 pounds of ivory – that’s about $19,000 per elephant.

You typically need 30-50 animals, bare minimum, to sustain a sufficient population of large beasts.

That’s a minimum ivory value of $570,000 to $950,000 per park.

Then there’s the issue of scarcity.

The price for ivory and keratin (what’s in your fingernails makes up rhino horn) will increase as the products become more scarce.

Would you pay a lot to go see rare animals in the wild?

Maybe, but I’d bet you’d be a lot more willing to book a trip if the chance of seeing those animals was high.

I paid a decent amount to get from a conference in Chennai to Kaziranga in Assam.

My friends estimated that bear viewing in Yellowstone brings in $10 million and adds 155 jobs to the economy each year.

I don’t know if rhinos, elephants, and tigers have that same effect in Kaziranga.

In the chaos of the tiger jam, we almost paid a similar price to the poachers who got caught by the Forest Guards.

4 Rhinos were killed in Kaziranga in the first half of January.

Tripp, I had no idea that poching was so bad today. I actually thought that all governments had cracked down on the ivory trade so severely that it simply had no value . How uninformed I am. Thanks