Marine debris: What are its effects and how do we solve the problem? This has been the topic of class discussion on two occasions so far during our time on Midway, and it has become clear to us future environmental managers that it’s an issue that will take a lot of ingenuity to fix!

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the United States Coast Guard define “marine debris” as: “any persistent, manufactured, or processed solid material that is directly or indirectly, intentionally or unintentionally, disposed of or abandoned into the marine environment.” Therefore, any item in the ocean that does not belong there is marine debris. You may have seen cigarette butts, drink containers, or plastic wrap on your favorite beach, either due to the carelessness of beach-goers or from waves bringing these items to shore. However, our class was shocked to observe firsthand the unfathomable amounts of debris (most of it plastic) here on Midway Atoll, a remote island far from large population centers. This plastic is either washed ashore during storms or brought onto land by the hundreds of thousands of nesting albatrosses, who mistakenly pick up plastic pieces from the ocean’s surface and feed them to their chicks.

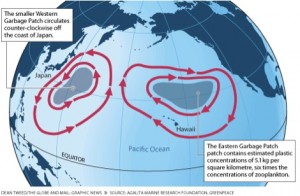

Since our oceans are all interconnected by the prevailing currents, marine debris originating in one part of the world could conceivably end up somewhere on the other side of the globe. For this reason, marine debris is an issue that we all experience and must grapple with. The five major oceanic gyres, which are vast areas of slowly circulating water, act as churning whirlpools that pull in marine debris and can keep it circulating there for years. The North Pacific Gyre is responsible for the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an area of particularly high densities of marine debris that occurs just north of the Hawaiian archipelago and overlaps with Midway albatross foraging grounds.

John Klavitter, wildlife biologist and interim refuge manager on Midway, has estimated that albatross parents here feed their chicks approximately five tons of plastic each year. These birds are unable to digest the plastic, and it remains in their stomachs, causing puncture wounds or false feelings of satiation. Many of the carcasses of young birds that litter Midway’s roads and paths have conspicuous plastic shards poking out from the bits of bones and feathers that remain. This was a grisly reminder to us that nothing that we put in the trash is ever really gone, and that our throwaway mentality has far-reaching consequences.

The first big question our class discussions on marine debris sought to answer was: how do we fix such a ubiquitous and persistent problem? Do we focus on cleaning up plastic that’s already in the environment, perhaps focusing on the garbage patches growing in the gyres and on our beaches and coastlines? Or do we stop the trash before it reaches the sea? The solutions we touched upon branched in several directions. There are technological innovations that would make at-sea cleanup more realizable, such as the Abundant Seas Foundation’s Pelagic Pod, which would float on the sea surface and filter plastic out of seawater that flows through its chamber. There are economic incentives such as Hawaii’s Nets-to-Energy program, which encourages fishers to bring their damaged gear ashore for conversion into electricity, instead of dumping it illegally at sea. Another crucial part of the solution is increasing public awareness of the issue, which can be done through organized beach cleanups and educational campaigns. These are just a few of the possible ways to reduce marine debris, and it will certainly require a combination of tactics to address the problem most effectively. We did all agree that marine debris needs to be addressed at the source, before it even becomes marine debris, rather than once it has already entered our waters and washed up onto our shores. What do you think are the most effective ways to reduce debris in our oceans? Have you seen examples of effective solutions?

Another topic we discussed was how to react to the albatrosses ingesting all this plastic and then feeding it to their chicks. Can we link albatross chick mortality to plastic debris consumption? Is this threat serious enough to have a population-level effect? We noted that there are many challenges in proving that plastic is responsible for chick mortality, and that in order for us to apply pressure on producers and legislators to make changes in how plastic products are manufactured and dealt with at the end of their life cycles, we would need hard evidence. Yet for this class out here on Midway, finding up to 80 pieces of plastic in the stomach of a dead year-old albatross is evidence enough that we are not properly addressing marine debris and much research and management expertise is needed. Good thing we’re graduating in May!

Recent research indicates that plastic in the ocean, while not a “garbage patch,” might be more of a problem as micro-plastic. Trying to filter it out of the ocean (like “There are technological innovations that would make at-sea cleanup more realizable, such as the Abundant Seas Foundation’s Pelagic Pod, which would float on the sea surface and filter plastic out of seawater that flows through its chamber”) might be more of a problem since plankton would also be removed?

Check out: “Ocean + Plastic = Trouble” at http://www.sciencebuzz.org/blog/ocean-plastic-trouble

Plastic in the environment is a huge problem; thanks for putting brainstorming power into finding solutions!

Hi Barb,

Thank you for your comment and for linking the article. You make a good point, and I should have been more specific in my description of what the Great Pacific Garbage Patch really looks like. The common misconception is that it is something more of a solid trash “island”, and indeed, calling it a “patch” is a misnomer. Yet as that website points out, the area of the North Pacific referred to as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch has concentrations of plastic debris that are significantly elevated than areas outside the patch. The floating debris mass shifts with wind and currents in predictable ways, and during storms, plastic from this patch ends up on beaches here in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. As you also mention, the garbage patch is composed of mostly very small pieces of plastic, because the waves, sunlight, and chemical reactions break larger items down. The Pelagic Pod is an idea that seems fanciful to some, and is not currently being used as a realistic solution to the problem, partly because the issue of scooping up plankton in the process is tough to avoid. But researcher Charles Moore of the Algalita Marine Research Foundation has shown that the ratio of plastic to plankton within the garbage patch is 6:1, so any decisions on at-sea clean-up will have to weigh the trade-off between leaving so much plastic out there and cleaning it out at the expense of plankton.

I’d be a little cautious in using Charles Moore as a source of detailed, accurate data. Imo, as a “citizen scientist,” he’s done a commendable job of alerting the world to the persistent problem of plastic in the ocean. However, I’d recommend such sites as these for more accurate info, especially after theyʻve had time to process the data from their expeditions–

http://hahana.soest.hawaii.edu/%5B…%5D/superhicat.html

http://sio.ucsd.edu/Expeditions/Seaplex/

http://www.sea.edu/plastics/index.htm

…and of course:

http://marinedebris.noaa.gov/info/faqs.html

I worry that when inaccurate hyperbole is used on the public, and later a more accurate but perhaps less spectacular picture comes into view, the public becomes even more skeptical of science.

Have a safe trip back to the East Coast; aloha, mālama pono,

Barb

I agree with your remark that exaggerations of scientific fact is not the way to garner public support, and I do my best to avoid such tactics. While Moore may be a “citizen scientist,” his data I reported previously (the six-to-one ratio) had been published in the respected, peer-reviewed journal, Marine Pollution Bulletin. If anyone is interested in reading that paper, please refer to:

Moore, C.J., Moore, S.L., Leecaster, M.K., & Weisberg, S.B. 2001. A comparison of plastic and plankton in the North Pacific Central Gyre. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 42, 1297-1300.