President Trump sees it as America’s ticket to a new era of “energy dominance.” New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy sees it as a dangerous source of water pollution that “should not have a role in the energy future of New Jersey.” Whichever side of American politics you stand on, chances are you, too, have strong opinions on fracking.

But what does fracking really mean for America’s energy system, economy, and environment? Is natural gas a “bridge fuel” to a clean energy future, or a ploy by Big Oil to keep us hooked on fossil fuels for another generation?

Few can answer that question better than author Daniel Raimi, a Duke alum who returned to campus last month to speak about his new book, The Fracking Debate: the Risks, Benefits, and Uncertainties of the Shale Revolution.

I grabbed a ticket to Raimi’s talk, hosted by Duke’s Energy Initiative, to hear his expert take on an industry that is polarizing not just along the political spectrum but even within the environmental community itself.

While researching his book, Raimi criss-crossed the country visiting rural communities-turned-fracking boomtowns from West Texas to northern Alaska, interviewing everyone from local officials to drill workers to bartenders. (Without any personal connections to many of the places he visited, Raimi spent a lot of evenings at bars.) And after all of his research, what’s the biggest thing Raimi thinks is missing from the fracking debate? Nuance.

“Whether you’re pro-fracking or anti-fracking,” Raimi said to begin his talk, “my goal is to make you see the other side of the debate.”

“Historic Highs”

The term “fracking” is shorthand for hydraulic fracturing, one of a number of innovations, including horizontal drilling and precise seismic mapping, that have together revolutionized America’s oil and gas industry.

According to the International Energy Agency, these technologies have paved the way for record-setting growth in US oil production. The US is poised to pump more oil than Saudi Arabia in 2018, and soon could be the biggest producer on the planet.

That sort of game-changing growth has real economic impacts, both globally and locally. While oil producer Venezuela’s economy has shrunk by half in the last five years as exports to the US plummet, North Dakota, home to the Bakken shale formation, is now the fastest growing US state.

Those economic benefits make fracking hard to resist in the communities where it takes root. Even in Barrow, Alaska, where melting permafrost due to climate change is literally destabilizing people’s homes, Raimi found that most residents still supported drilling.

Beware the Happy Hour Effect

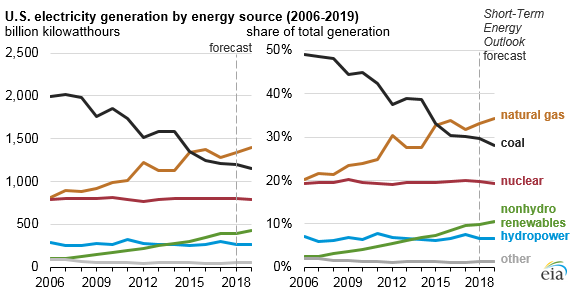

Booming domestic production means that oil and gas are now cheap. In some ways, this has been good for the environment: natural gas has overtaken coal as the dominant fuel for power plants across the country, and carbon emissions from the electricity sector are at their lowest level in 25 years.

But low-cost fuel also opens the door for what Raimi calls the “happy hour effect.” When drinks are cheaper, people drink more; when gas is cheaper, consumption rises in the same way. If Americans take advantage of happy-hour prices at the pump, though, the carbon consequences could be worse than a Sunday morning hangover.

The happy hour effect, combined with leaking methane from gas wells, complicates the relationship between fracking and carbon emissions. While the move from coal to gas in the electric sector provides climate benefits in the short term, Raimi said that long-term, fracking may have little net impact one way or another on the warming climate.

Opening the Door

Regardless of natural gas’ direct impact on carbon emissions, Raimi sees one way that cheap fuel can provide an opportunity for action on climate change.

“The availability of low-cost natural gas, regardless of which administration is in power, I believe makes it less costly and easier to implement [climate change] policies,” Raimi said in a recent radio interview. He cited the success of cap-and-trade programs designed to reduce carbon emissions in California and the northeast, as well as new plans to put a price on carbon in Washington and Oregon.

But, he added, even if fracking has opened the door to enact climate policies with a lower price tag, whether or not those policies are actually implemented still depends on the “prevailing political winds.”

At the end of the day, fracking technology does not dictate the role it plays in the fight against climate change. Will we gorge ourselves on oil at happy hour prices? Or will we push for policies to cut carbon while the cost of doing so is low?

That power is in our hands.