It was my second day in Kazakhstan. The ubiquity of Cyrillic text and Russian and Kazakh conversation made North Carolina seem far away. I sat in the airport in Almaty (the financial capital) waiting to fly to Astana (the actual capital) for some meetings at the US Embassy.

The entire domestic boarding area was small – only two little stores. Sipping tea at one of the tables, you could look directly back through the unimposing security line to the check-in counters beyond them. Different as all this was, the woman attempting to navigate the check-in line with her new husband struck me as even more unusual.

I think I first noticed the large, flowing, white dress, and only after that, the woman wearing it. Next I took in the veil, lace gloves, and earrings. They don’t make you take your laptop out of its bag at domestic check-in in Almaty, Kazakhstan, but this newlywed, and her husband, in an authentic Russian shiny tuxedo replete with a thick, thick tie, still earned themselves a private screening.

They came through without problems.

I had so many questions about why someone would be wearing their full wedding outfits to take a flight on a Thursday morning. I asked people about it at the airport and in the capital. No one to whom I spoke had any understanding of their behavior either.

Kazakhstan is one of the places, like many in the US today, where you can get stopped and asked for your documents because you look different or because the police are bored.

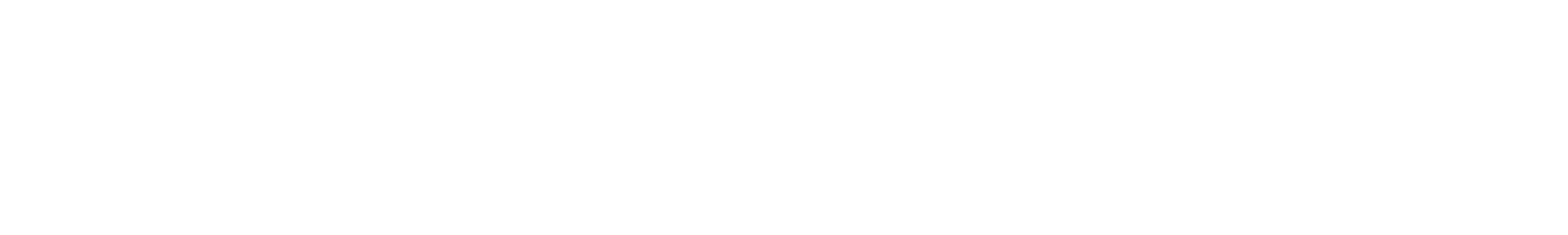

I lived in the capital of the easternmost province, not too far from Kazakhstan’s borders with Russia, China, and its almost border with Mongolia. This diagonal meeting of nations resembles the cross on the battle flag of the Army of Northern Virginia, more commonly known as “the Confederate flag.”

My name, Tripp, often elicits questions after introductions. It strikes most everyone as strange. Non-English speakers tend to have a hard time pronouncing it. Skilled Anglophones lounging around various hostels often assume it is a sort of Appalachian-Trail-style name that has been bestowed upon me on the road.

In the American North, after getting to know me a bit, people would often ask, whatthehell doesyournamemean? Any kid from the South, my home, could have told them that I have the same name as my father and my grandfather. “I’m the third, like triple.” And my automatic follow-up these days, “It’s a thing we do in the South.”

In my mind, sometimes my greeting is “Hi, my name is ‘from the South.’”

When people will ask me “Where in America are you from?” they will often expect me to say “California.” Though I am a North Carolinian, abroad, I would sometimes try out Atlanta.

The ’96 Olympics, Coca-Cola headquarters – it seems like a recognizable city. Certainly more prominent than Raleigh, North Carolina. But Atlanta doesn’t even make the radar in Kazakhstan, or India, or Namibia. When I venture to say just the state of North Carolina, people think I live near Canada.

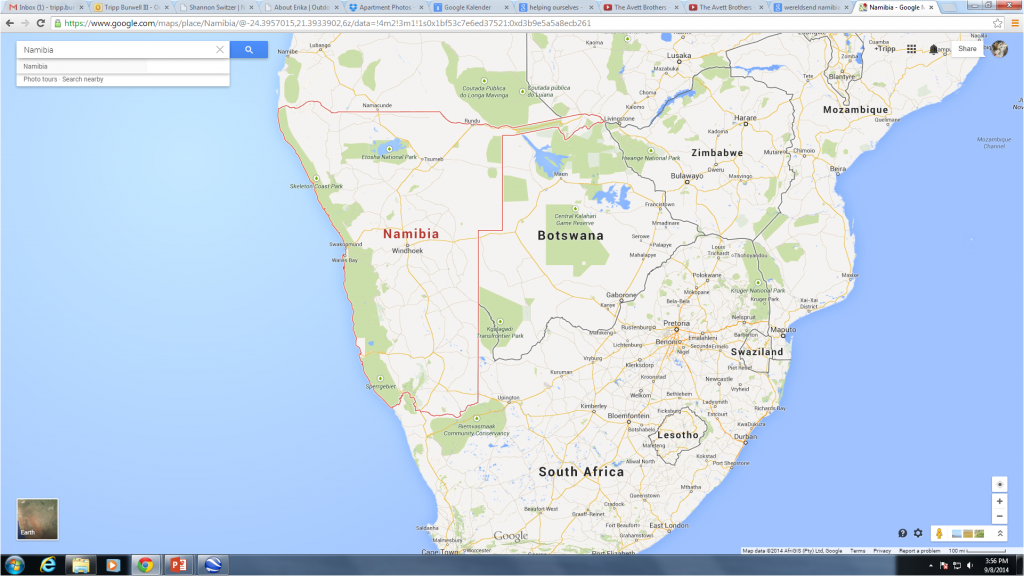

Though not an Olympic sport, rugby often elicits fervent passion in many places I have worked. I was studying abroad in Namibia in 2007 when South Africa beat England in the Rugby World Cup. During halftime, we were thinking about going outside to stretch our legs, but an elephant knocked over a substantial tree planted outside the house and we decided to stay inside. Namibia is a desert country in south-west Africa, bordering South Africa to the north-west.

Namibia and South Africa have had a pretty complex relationship, starting during World War I, when South Africa captured the colony of Namibia from the Germans. It ruled Namibia for 75 years, until 1990.

From 1966-88, Namibia fought a guerrilla war for independence from South African apartheid rule. In one example of typical apartheid brutality, there are many stories of South Africa’s occupying police force – the South Africa Defence Force – using black Namibians for target practice in some of the large empty portions of the sparsely populated country.

Watching various games of the Rugby World Cup with black Namibians, victims in many other ways as well, I noticed that they would always offer full-throated support for the South African side, less than 20 years prior their brutal colonizers and oppressors. I couldn’t help but contrast their experiences and attitudes with my own understanding of the history of Reconstruction.

And everything since then.

I sometimes wonder how long it would have taken us to pull for an explicitly Northern side, or if we even are yet.

According to the 1860 census, the greatest numbers of slaves in North Carolina were clustered in the northern and eastern part of the state, where my dad’s side of the family is from. The slideshow below demonstrates how the slaves became concentrated in that area over the first 70 years of the US’s nationhood.

Slaves constituted a majority of the population in thirteen of North Carolina’s then 87 counties. According to November 2013 Bureau of Labor Statistics data, of those thirteen former majority slave counties, all but the one county (Franklin) neighboring the capital had above average unemployment rates today. In six of them, more than 10% of people cannot find work.

90 of the 100 counties in North Carolina reported data on citizens living below the poverty level in 2012.

In every one of those 90 counties in North Carolina, a greater percentage of the black population lives below the poverty level than the percentage of the white population that also lives in poverty.

After last year’s shutdown of the federal government, Ryan Lizza observed in the New Yorker that the clearest difference between Republicans who had signed onto a pledge to defund the Affordable Care Act, even if it meant shutting down the government, and those Republicans who voted to open the government again was “the oldest divide in American politics: North-South.”

Many of my friends from the North, where I studied and worked for a while, tell me that Southerners can’t tolerate a “black man in the White House,” emphasizing the contrast between black and white, as if I couldn’t deduce that fully one-third of the words in that phrase were antonyms. Stop patronizing the South, I tell them. Your view is as simplistic as the one you’re trying to paint on my region.

At some point, however, after all the actions of the North Carolina legislature and the accompanying Moral Monday protests in my hometown of Raleigh, I began to wonder. However you feel about it, governments representing the people of the South (and in some other parts of the country) have made it more difficult for some people to vote and harder for others to get married.

The disenfranchisement from our current state legislature seems to carry a particular bias towards African-Americans, as the new laws create more negative consequences for them than the rest of the population. Perhaps, as the Supreme Court argued in striking down the Voting Rights Bill, we are closer to equality than we’ve ever been before. We don’t need to make the same considerations as we used to.

Or, perhaps, as Ta-Nehisi Coates has argued, the equality backlog is so huge that we are nowhere near close to making it right.

Demographic facts support Mr. Coates and suggest that things may not have changed as much as many of us think.

Back in Kazakhstan, I continued on my way to Astana, the capital. The day after the newlyweds got on an airplane in their wedding clothes on a weekday morning, I saw something that struck me just as out of place as that couple. I was at the US Embassy for some meetings (locals have nicknamed it Alcatraz due to its fortifications). Inside, the flags of the 50 states hang a few floors up over a foyer.

In between meetings, I was talking with a Kazakh local. While standing under these flags, she asked me which state I was from. I said North Carolina and went to point out our state flag, based on an 1861 design. While doing so, I saw Mississippi’s flag, which has donated much of its field to the “Confederate flag.”

I thought about trying to explain some of the history of the battle flag of the Army of Northern Virginia, but decided against it. For some, reason, it now jarred me. After all the things I had trouble explaining or understanding, I at least knew what I didn’t want to say.

I didn’t really want the definition of my region to the outside world to continue to be about that particular flag and its residue.

Tripp I am so impressed .hope you will continue to write and keep us posted on your interesting travels.